A House in Perfect Order: How Cary Grant Reimagined Domestic Life

Images Courtesy of Anthony Barcelo New York Post

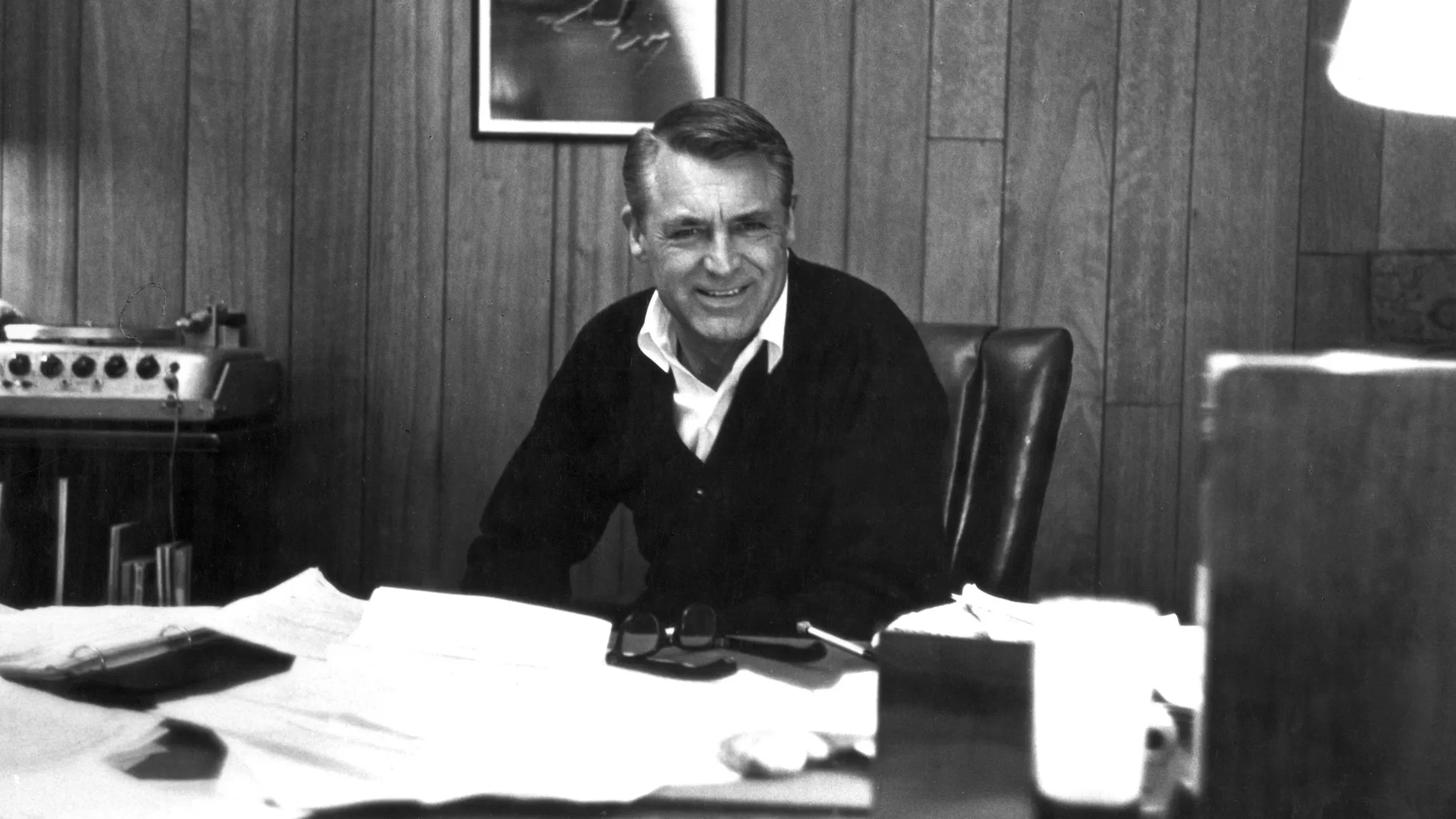

When Cary Grant bought a modest estate in 1946, he transformed it not into a palace of celebrity excess, but into a study in symmetry, restraint, and control—his clearest performance of all.

City skyline viewed from a rooftop pool with four lounge chairs and small tables during dusk.

Empty tennis court with a net and modern apartment complex in the background, under a blue sky with some clouds.

Some men buy houses. Cary Grant bought vantage points. He didn’t so much acquire real estate as select his role in the landscape. When he purchased the Beverly Hills estate in 1946—a year after V-J Day, at the precise hour America began to believe in leisure again—it was not yet the stuccoed Xanadu it would later become. It was a low-roofed, badly-planned, vaguely Italianate nothing. But it sat high enough above Benedict Canyon to remind an Englishman of the distant abstraction of empire. This was a house not of now, but of future possibility.

Grant, born Archibald Leach in the soot-soaked tenements of Bristol, understood artifice better than anyone in the city of illusions. He had spent his life remaking himself, each iteration closer to the man the world expected. He was not interested in comfort, per se. He was interested in control.

So he had the ceilings raised. The walls reoriented. The views from the master suite recalibrated to catch the last slit of Pacific light. The estate became a cinematic set for domesticity: hedges pruned into formality, interiors stripped of clutter, all clean lines and latent performance. He didn’t live in it so much as occupy it with careful precision.

This was the home he shared with his fourth wife, Barbara Harris—35 years his junior and, by all accounts, more interested in the Cary Grant behind closed doors than the one smiling on a Columbia backlot. She later described their life there as “happily cloistered,” though no cloister had quite such guests. There was, for instance, the night of her surprise birthday party when Frank Sinatra and Gregory Peck—having forgotten the code for the new wrought-iron gate—simply crawled through the shrubbery and in through a window. The house, so elegant in daylight, became a playground for mid-century America’s demi-gods after dark.

At the time of purchase, Grant had just come off a streak of films that cemented his double identity: Arsenic and Old Lace, None But the Lonely Heart, and soon after, Notorious. These were roles that blurred the line between menace and suavity, between clown and gentleman. It’s tempting to think the house shared something of that ambiguity. It was beautiful, but never soft. It offered comfort, but not indulgence.

One morning in 1948, while hosting Noël Coward and David Niven for breakfast on the stone terrace (Niven stayed for three weeks, having “lost” his own home to a lover’s quarrel), Grant disappeared mid-conversation. He returned wearing a garden hat and holding a Japanese hoe. "You’re guests,” he said, “but I’m the groundskeeper." This, reportedly, was not a joke. The citrus trees needed pruning. There was soil under Cary Grant’s fingernails long before there was LSD in his bloodstream.

Yes, LSD. By the mid-1950s, Grant had entered the era of his controlled hallucinogen experiments—undertaken in Hollywood-quiet therapy offices while still living in the house. He would later credit those sessions with helping him "see the light." But perhaps it was the architecture that first led him there.

To understand the house is to understand Grant’s need for precision: every stone aligned, every sightline framed. He had made a career of being watched; here, he built a life that watched back. The interiors were subdued: cream upholstery, Japanese ceramics, a scattering of antique English mirrors. There was a weight to the simplicity. A studied reserve that said: here is a man who has had enough of being adored, and who now wishes simply to edit the air around him.

Actor Cary Grant at his house office, in Beverly Hills, 1964.

The house in 1946

The house remained his primary home until his death in 1986. It passed from view, like its owner often tried to. What remains is not just a Hollywood mansion, not even a monument to stardom, but a precise expression of its inhabitant: a man in retreat from noise, designing the conditions of his own stillness.

And it had to have a good view. Cary Grant, above all, knew that every performance needs an audience—even if it’s just the horizon.

Now listed for $77.5 million with Christies International Real Estate, the estate has undergone an extensive transformation far beyond Grant’s original refinements. Reimagined by architect Corey Gordon and designer David Phoenix, the property now spans nearly 11,000 square feet, with seven bedrooms, a new guest house, a state-of-the-art wellness pavilion, and manicured grounds that would make even Grant’s fastidious garden shears blush. While the soul of the house once rested in its restraint, the current iteration leans into scale and spectacle—less groundskeeper, more Gatsby.

"You’re guests,” he said, “but I’m the groundskeeper."

Images Courtesy of Anthony Barcelo New York Post

-

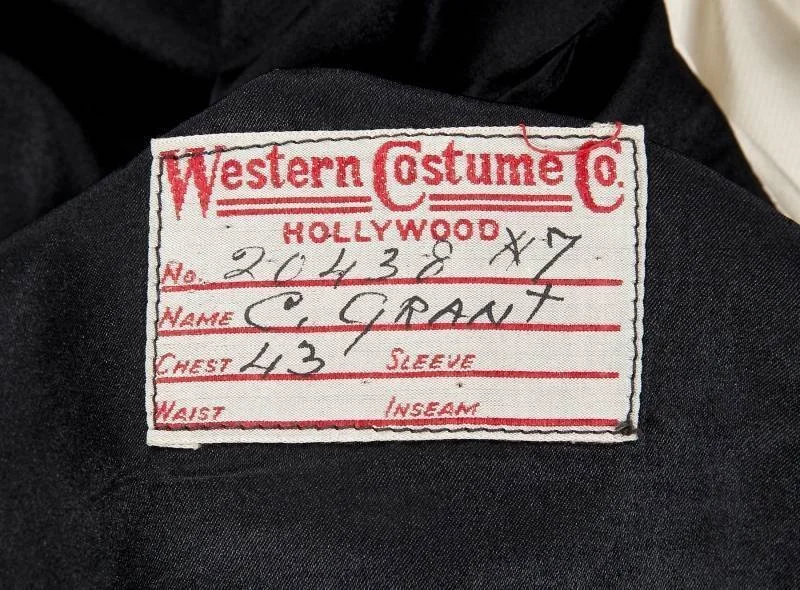

Two period jackets made for Cary Grant.

Estimate $600 / Sold $4160

-

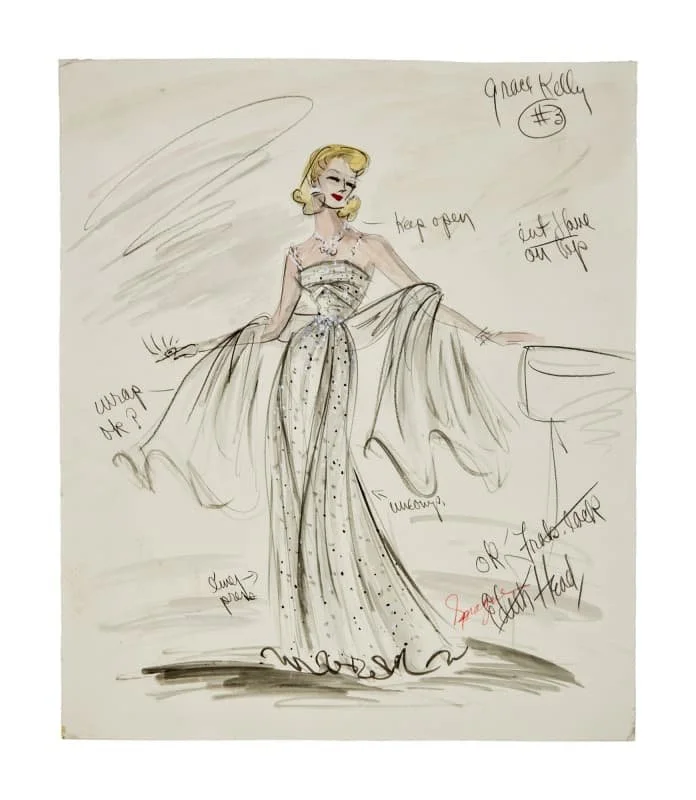

Alfred Hitchcock "To Catch A Thief" Edith Head Signed White Gown Costume Illustration.

Estimate $5000 / Sold $34,925

-

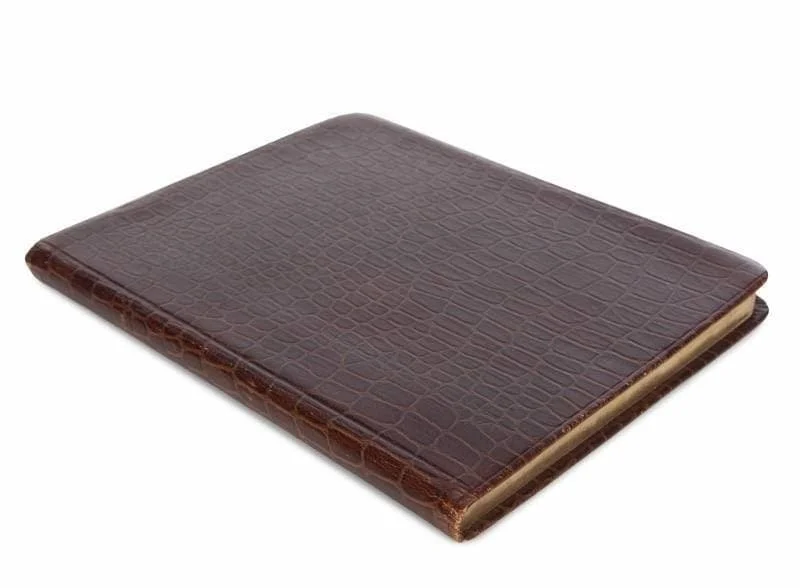

Cary Grant’s personal autograph book. The leather book contains over 20 signatures from Grant’s celebrity associates

Sold $2813

-

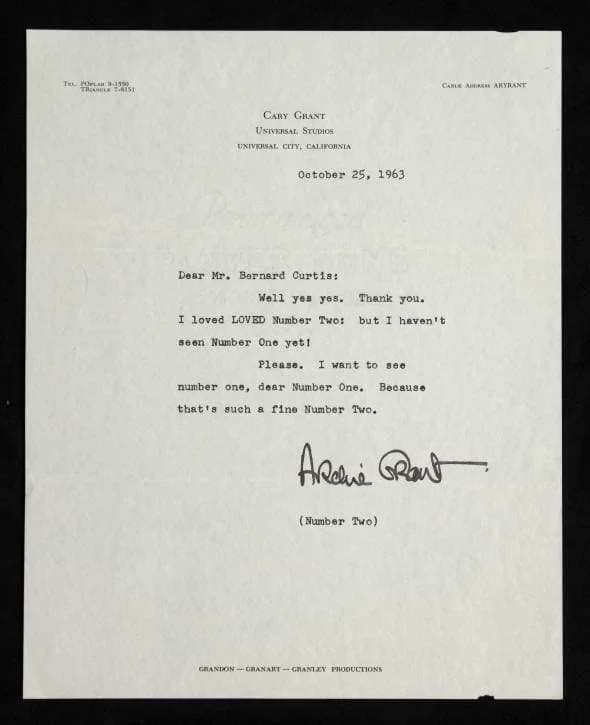

A typed letter to "Mr. Bernard Curtis." Signed "Archie Grant" in ink, dated 1963.

Estimate $200 / Sold $1500

-

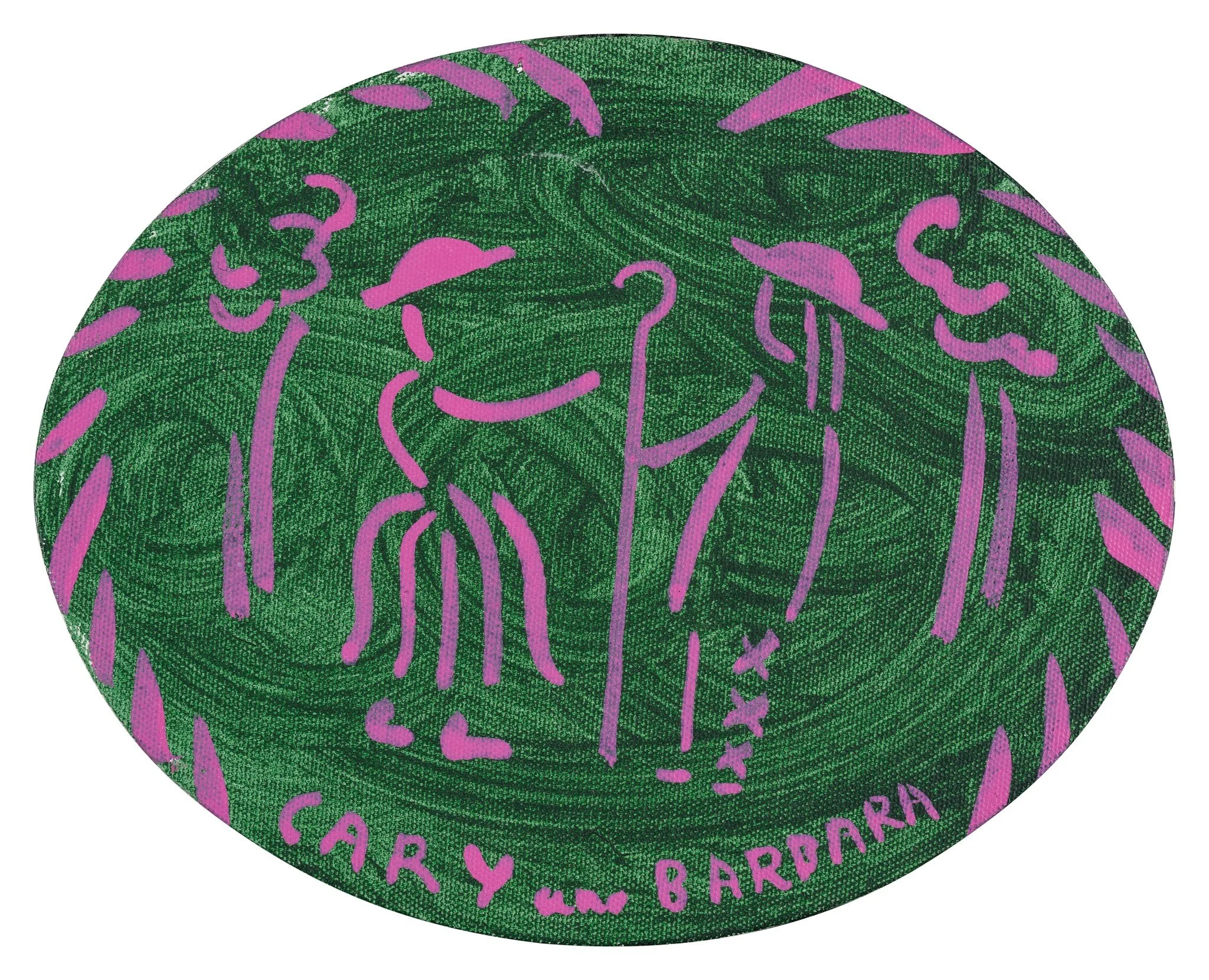

David Hockney inscribed “Love from Grant”. From the Collection of Barbara Grant Jaynes, the Former Mrs. Cary Grant

Estimate $10,000 / Sold $24,000

-

This lobby card—known by collectors as 'the crop duster' card—is the most sought-after from the set of eight US lobby cards.

Sold £882