Inside the Lichtenstein Collection: A Portrait in Objects

All Images Courtesy of Bonhams

From Matisse drawings to a paint-splattered studio chair, the Bonhams auction of Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein’s personal collection reveals how artists live not just with art—but in conversation with it.

MALCOLM MORLEY (1931-2018) Lifeboat IV, 2009

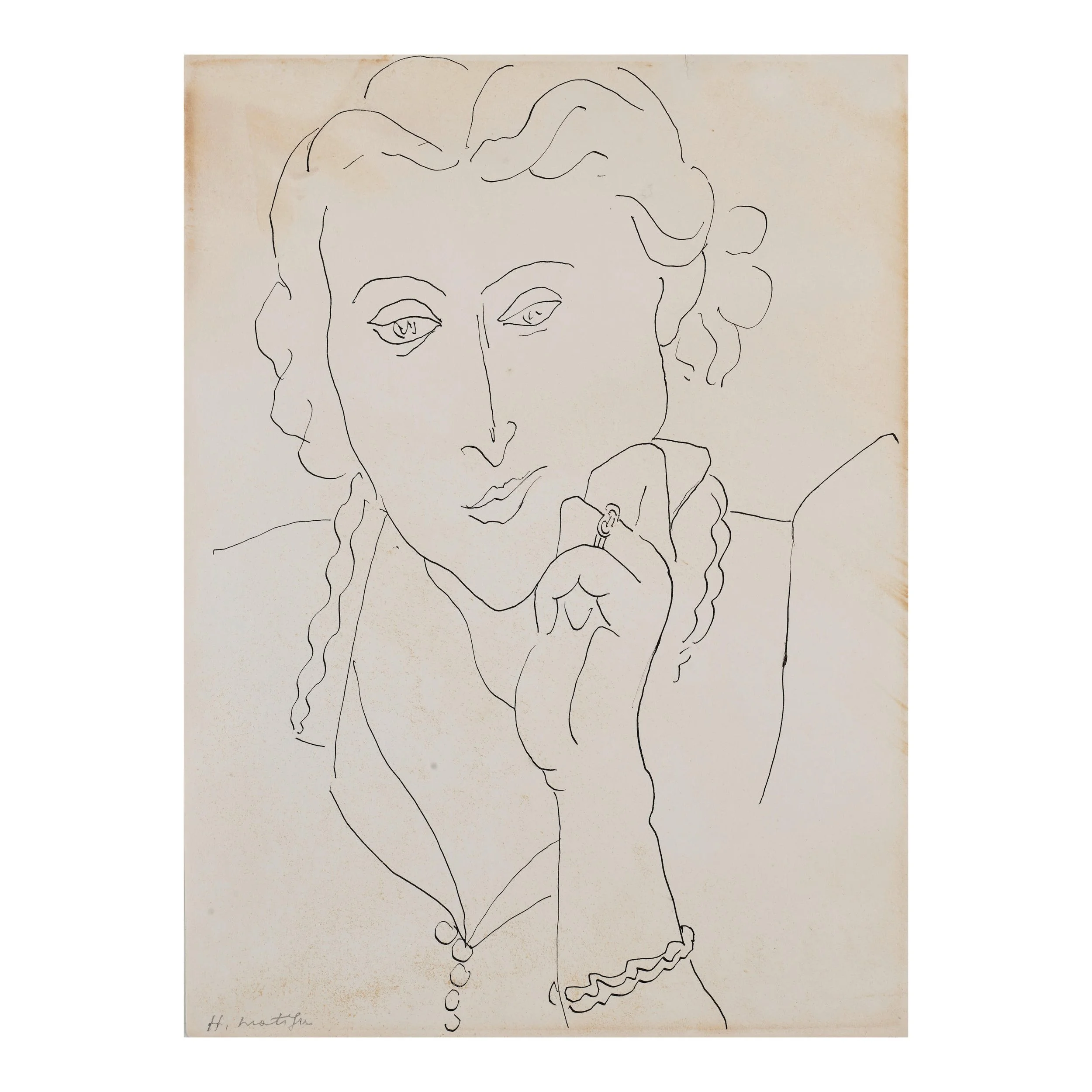

HENRI MATISSE (1869-1954) Portrait de femme accoudée

There’s something revealing—intimately, almost indecently so—about the objects an artist chooses to live with. Not those they make, but those they keep. What hangs above their beds, what rests beneath their coffee cups, what they place quietly in the corner of a windowless hallway. The Bonhams auction, Dorothy and Roy Lichtenstein at Home: The Personal Collection, gives us a chance not to observe the works of Roy Lichtenstein, but rather to observe the works that observed him—the art and objects that, in silence and over time, witnessed the everyday rhythm of a maker.

When Roy and Dorothy purchased their Southampton home in 1971—a former carriage house on Gin Lane—it was not with fanfare or foresight of property appreciation, but with the gentle gravity of artists recognising a place where their lives could unfold. “We came for several summers,” Roy once said, “and one fall just didn’t leave.” That is how artists settle: by accident, by longing, by the quiet magnetism of somewhere that understands their pace.

The house itself was a haven—both for Roy’s making and for their living. There was a separate studio where his hand found its comic-book rigour, and there was the carriage house, filled gradually with Matisse drawings, Kelly abstractions, and spongeware bowls. If the studio was Roy’s public mind, this home was their shared subconscious.

What is striking is not the grandeur of the collection, though it is formidable—Jasper Johns’s Flag (Moratorium), Rauschenberg’s defiance, the crisp restraint of Ellsworth Kelly’s Blue Curve. It is the tenderness of the collecting. Dorothy said they loved drawings because you could “really see the hand of the artist.” This wasn't a performance of taste. It was an intimacy of seeing. And what are drawings, really, but hesitations made visible?

Art historians often circle the big question: What do artists make? But this collection turns the question slightly, more humanely: What do artists choose to live with? What pulls at their eye when it is at rest?

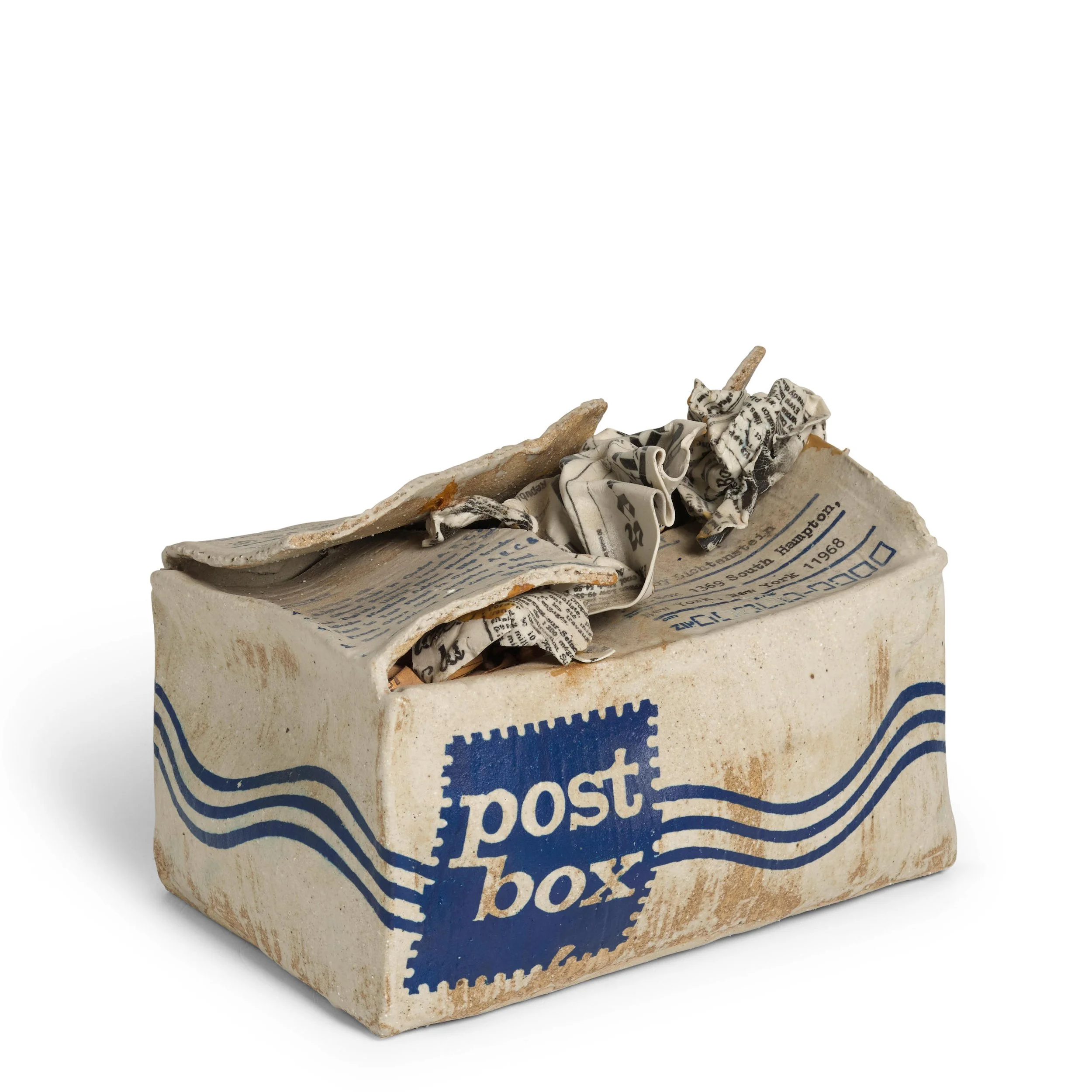

TONY BERLANT (B. 1941) Untitled (House)

Decorative paper house with butterfly and fruit illustrations, including strawberries, apples, and various butterflies.

DAVID HOCKNEY (B. 1937) Celia Reclining

A GROUP OF DESK ORNAMENTS

There’s something deeply moving about the modest objects too—a studio chair, paint-splattered and unremarkable, bearing the weight of thousands of hours. Blue and white spongeware, not expensive, not rare, but repeated—used. A bookshelf lined with art books, their spines softened, their margins likely annotated. These are the artefacts of a life not just in art, but with art.

Theirs was not a collector’s collection. It was a conversation. Many of the artists whose works hung on their walls were friends. Johns. Rauschenberg. Kelly. Their home was a site of exchange—not just of artworks, but of afternoons, phone calls, debates, drinks, silences. Dorothy once said, “No one thought they were going to make it big. You’d made it if you didn’t have to drive a cab.” That humility, that quiet defiance of the future’s verdict, saturates the collection.

Compare, for instance, with someone like David Hockney, who collected photography; or Cy Twombly, who clipped scraps of Greek poetry. The collections tell us: “Here is what I think matters, what I feel in my bones.” For Roy and Dorothy, it was the lineage of abstraction and pop, the dialogue between comic and classic, gesture and form.

And yet, there was a vision. A belief that beauty, simplicity, and seclusion mattered. Before Southampton was The Hamptons, it was a refuge. Artists came not to be seen, but to see better. Roy made his most iconic works—Brushstrokes, Sunrise, Imperfects—in that studio, with that light, that silence.

ELLSWORTH KELLY (1923-2015) Coloured Paper Image XVI (Blue Yellow Red)

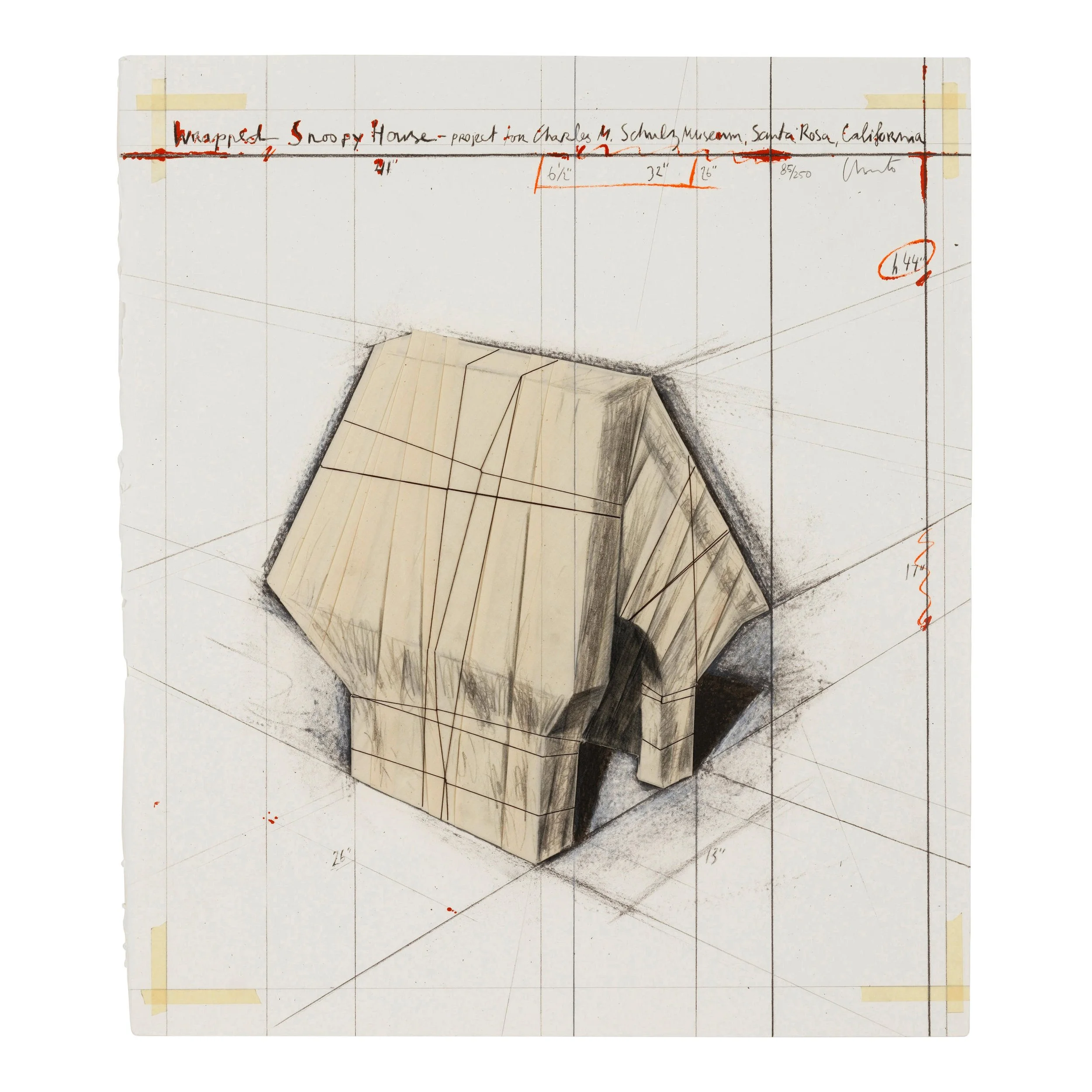

KIMIYO MISHIMA (1932-2024) Post Box to Roy Lichtenstein

Now, as Bonhams stewards this collection, the objects begin a second life, a dispersal. But they are still charged. They carry the residue of looking. They are the relics not of fame, but of attention.

What does an artist collect? Not trophies. Not ornaments. They collect evidence. Of friendship. Of influence. Of time. And, above all, they collect that which watches them back.

"To see is to place yourself in relation to that which is seen," John Berger once wrote.

Roy and Dorothy saw—and were seen—in these objects.

Now, so do we.

Ending 30 July 2025, 12:00 EDT with Bonhams

"When we collected, we collected mostly drawings," Dorothy once said, “because you could really see the hand of the artist.”

JASPER JOHNS (B. 1930) Flag (Moratorium), 1969

All Images Courtesy of Bonhams