The Bag That Remembered Her: Jane Birkin’s Original Goes to Auction

Image Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Jane Birkin’s original Hermès bag—scratched, heavy, and half-forgotten—sold in Paris for €8.6 million. What they bought wasn’t just the bag. It was the weathered outline of a life.

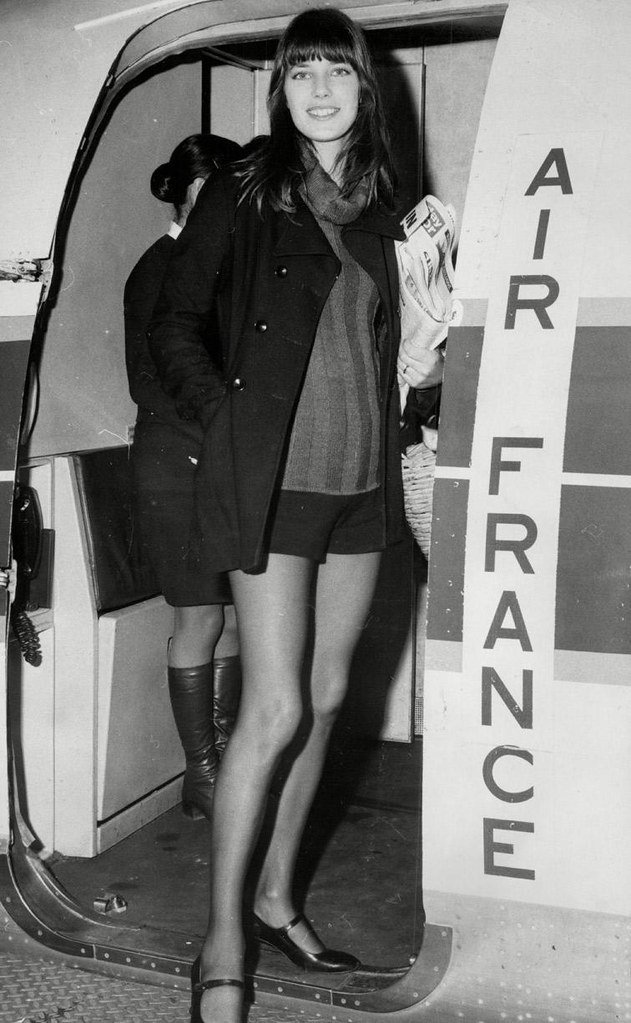

Jane Birkin and Bag

On a rainy Thursday in early July, in a softly lit room at Sotheby’s Paris, a battered black leather handbag once carried by Jane Birkin sold for €8.6 million. The price, a record for any fashion accessory sold in Europe, whispered its meaning into the hushed chamber. It spoke not only of opulence or cultural cachet, but of the intersecting forces of desire, memory, and myth that swirl around objects of our collective imagination.

This Birkin was no ordinary bag. It was the prototype—the original. Designed out of a chance encounter between Birkin and Hermès’s then-CEO Jean‑Louis Dumas, sketched on a vomit bag at 30,000 feet, and worn by Birkin for nine years. In those years, an “ordinary” handbag became an artifact of personal history: scratched, stickered, carried through streets and through celebrity. It wore its life visibly—an aura that polished luxury cannot replicate.

Sotheby’s Morgane Halimi called the sale “a startling demonstration of the power of a legend,” and indeed it was. Somewhere between the hammer’s fall and the pounding of the gavel, there was a collision of biography and economics, of name-brand mythology and individual narrative. Nine bidders—some on the phones, some online—competed. A private Japanese collector emerged victorious. Through wires and screens, Birkin’s myth travelled once more, from her arms to a global collector’s cabinet.

Jane Birkin, who died in 2023, would have been 78. Her life, as public as a Paris protest, stretched decades beyond that flight in the early 1980s. She was rarely photographed without the bag that bore her name—though she later disparaged it as “bloody heavy” and, with characteristic candor, asked Hermès to withdraw her name from crocodile versions on ethical grounds. Her ambivalence—a telling counterpoint to the couture machine that named the bag after her—reminds us that the artifacts we collect often outlive both their makers and their muses. The Birkin bag, now priced somewhere between a rare Monet and the ruby slippers of Dorothy, occupies a realm of its own: one part handbag, two parts time capsule.

Birkin gave the prototype to auction in 1994 for an AIDS charity and it later wound up with Catherine B., the Parisian collector whose own dedication to provenance and cause created another chapter in the bag’s litany. The bag has been exhibited at MoMA and the V&A, and still bears the nail clippers Birkin stashed within. These details give texture: the folds of a life lived, not just a brand advertised.

What does it mean that the world paid €8.6 million for something used, imperfect, and intimately worn? It means that certain objects straddle private memory and public myth so vividly they accrue value no marketing budget can conjure. That the Birkin bag is—despite or because of its imperfections—more genuine. It asks us to reconcile the romance of provenance with the cold arithmetic of auction houses.

There is, too, an irony. Hermès carefully cultivates scarcity: “tying” customers to spend heavily elsewhere, managing waitlists like ancient gatekeepers, stamping each bag by hand with artisan skill. This provenance-schizophrenia—intentional exclusivity paired with celebrity fueled hype—creates a dynamic we understand well in another world: fine watches, art, rare books. None escape the translation of scarcity into value. But this particular bag is different—it was born from an idea, sketched mid-flight, and its imperfections are part of its pedigree .

It is tempting, perhaps easy now, to reduce the auction to glib commentary about conspicuous consumption or posthumous profiteering. And yet begrudging that the market paid €8 million for a scuffed icon is to miss the nuance. We pay for provenance because it is history made palpable. This Birkin is not a mass-produced object; it is a one-off, a first draft, and that matters. It is the difference between seeing a photograph of the Eiffel Tower and climbing its iron stairwells. The feeling cannot be replicated .

For Hermès, there is perhaps both triumph and loss here—a triumph in seeing the brand honored; a loss in the realization that the “Birkin” can transcend its maker. Jean‑Louis Dumas offered a symmetrical gamble on that flight: did he expect Birkin’s name would eclipse the Kelly? We cannot know. But looking at the finished product, branded articles and script initials, we can see why she did.

We live in an age of curated scarcity. The Birkin, like a rare timepiece or a limited edition Vuitton trunk, is a proof point: privileged access, a series of gatekeepers, the promise of timelessness. Yet the auction’s emotional undertow—collectors moved, bidders moved, the room gasped—reveals something more. The value here was narrative—Birkin’s story, her charm, her resistance to excess.

When the hammer finally descended, those who paid did not purchase leather and brass. They purchased the idea of that young singer, a poet of French mid-century cool, whose messy, casual indifference created a template for desirability. Orphaned of its maker but not of its significance, the bag was reborn as artifact.

The buyer was soon revealed: Shinsuke Sakimoto, a former professional footballer turned CEO of Japanese luxury resale giant Valuence Holdings. His was not the acquisition of a collector quietly tucking a prize into a safe. It was a public gesture. Sakimoto has said. The win was deliberate, designed for the theatre of the auction room and the echo chamber beyond it.

For Sakimoto, the bag is both trophy and talisman. He says it will never be resold, only displayed — a corporate heirloom, a conversation piece in the firm’s campaign for “circular luxury.” But the numbers tell their own story: by his estimate, the media coverage and brand lift will generate an eight‑figure sum in advertising value over the next decade.

This is the quiet truth about the sale: the record price was not only for the bag but for the event of buying the bag. Auction rooms have become not just marketplaces but stages. In recent years, the most successful resale players have learned that a spectacular acquisition can be as valuable as the thing itself. A bag that will never be resold can still yield returns — in coverage, in prestige, in the shifting calculus of who is seen to own what.

And so the Birkin moves from Birkin’s arm to the vaults and vitrines of a resale empire, preserved not as a personal possession but as a public emblem. The point, as always, is not the object itself but the story it carries — and the stories still to be told about the carrying.

A final thought: this Birkin bag, imperfect yet consecrated, reminds us of the small humanity at the heart of high fashion. It is, in the end, not the symbol, but the story that matters most.

“They didn’t want the bag.

They wanted the life it carried.”

All Images Courtesy of Sotheby’s