Cassavetes’ House Is for Sale. But You Can’t Buy the Magic.

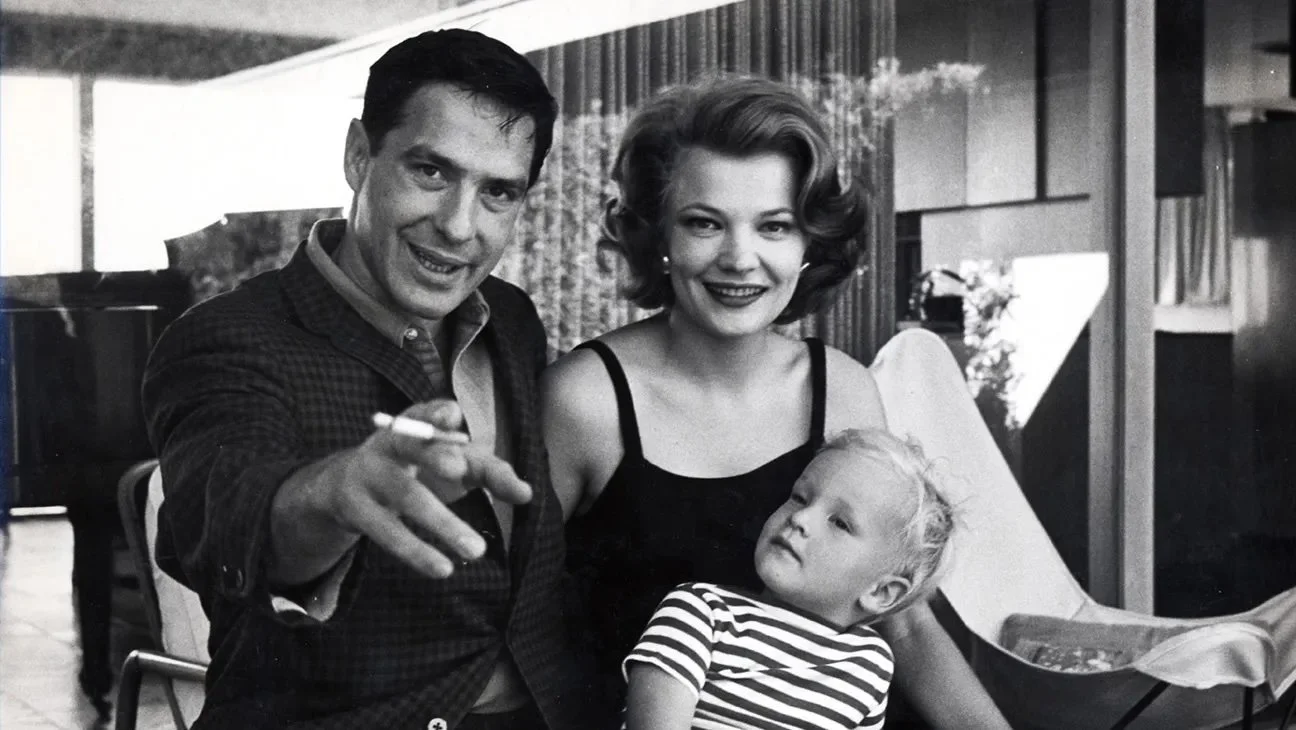

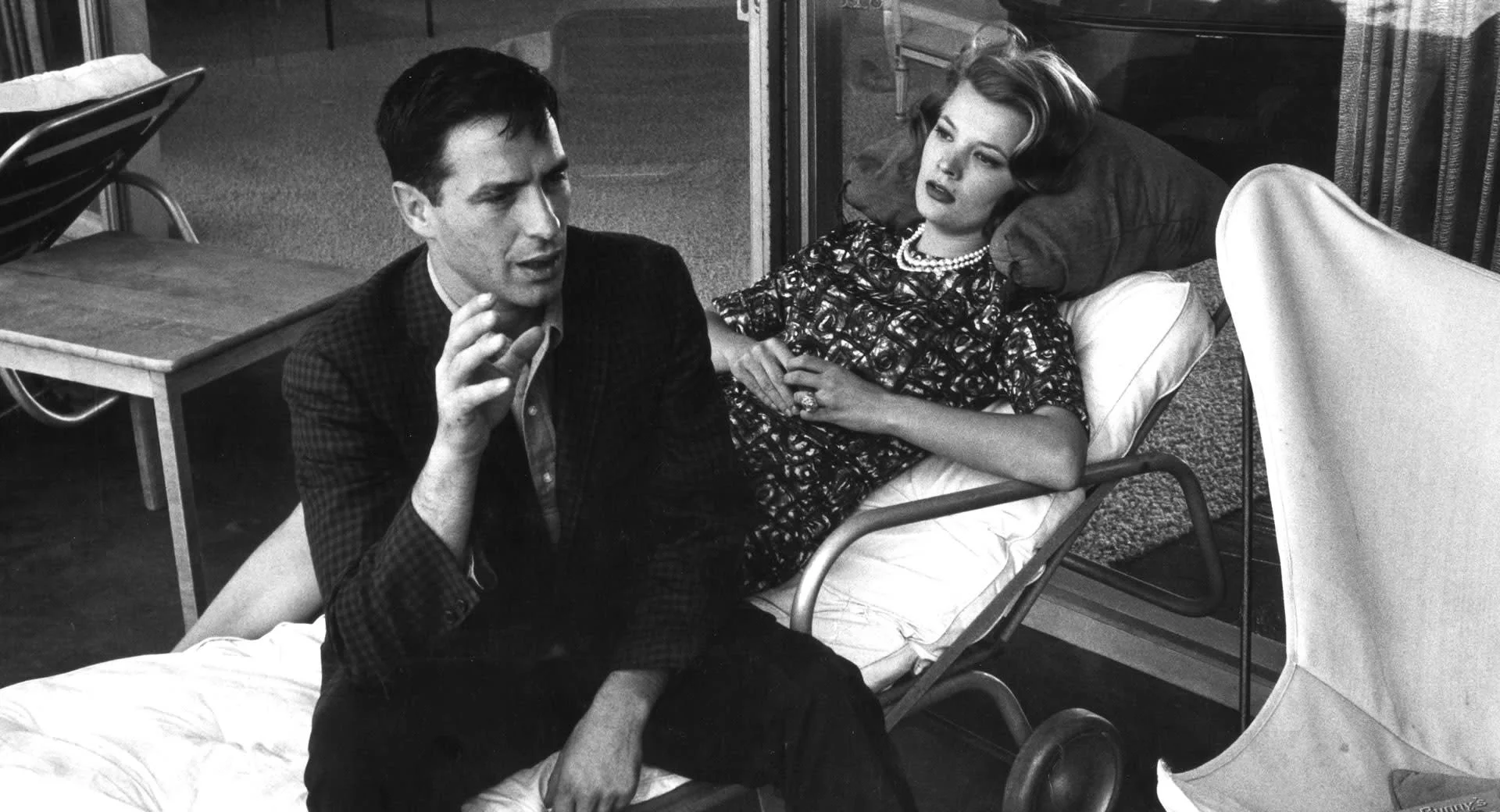

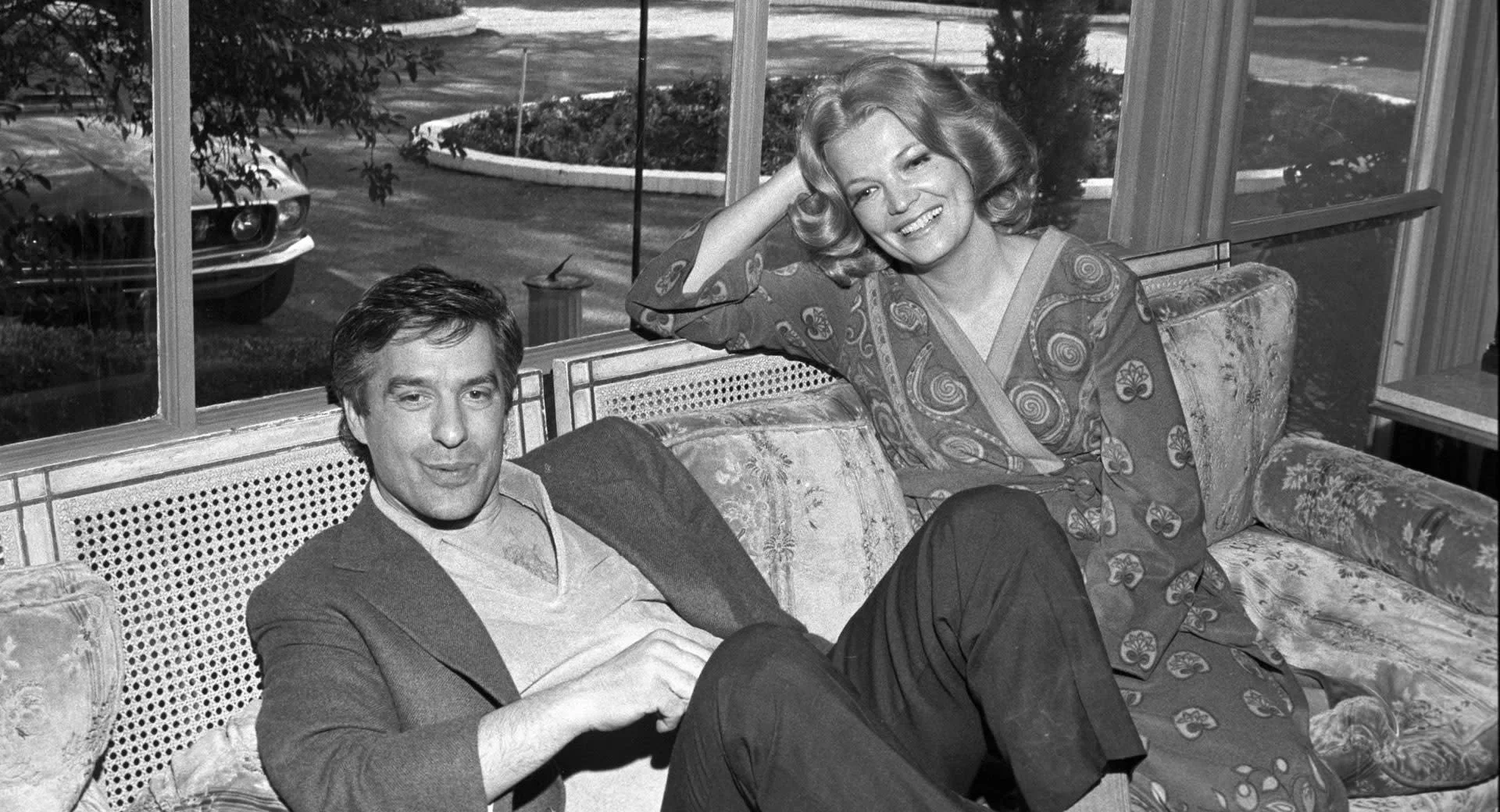

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowland in their Hollywood home

Inside the quiet Hollywood home where John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands redefined American independent film—and why its sale marks the end of something far less tangible than real estate.

You could say it was just a house. Four bedrooms. A bar. A pool with no edge. But that would miss the point. The point is how it was used.

You don’t stumble onto a property like 7917 Woodrow Wilson Drive. You go looking. Past the gate. Up the long drive. Trees, still. Light, scattered. What you find isn’t showy, isn’t waiting to be seen. It is quiet. It knows what it has witnessed.

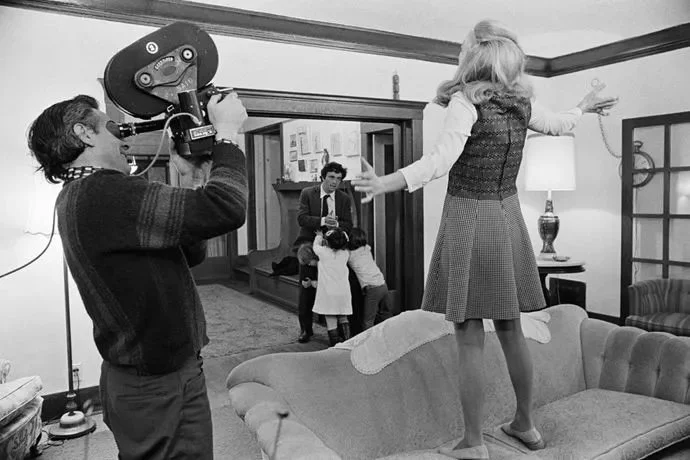

John Cassavetes bought the house in 1960. Gena Rowlands lived there until she died. They raised children here. They made films in the living room. The kinds of films that didn’t apologize for being difficult. Or loud. Or strange. That sort of work requires space—not just physical, but psychic. The house gave them both.

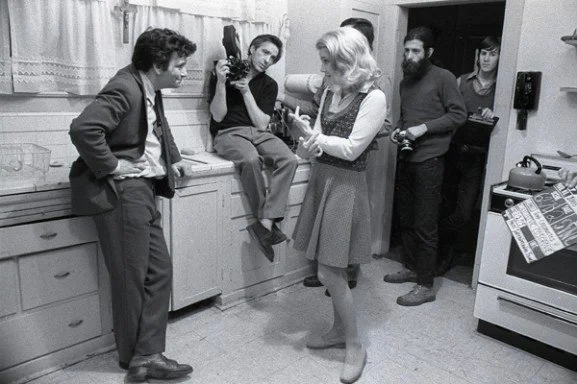

Cassavetes made movies with the lights left on and the camera still rolling, after the dialogue had frayed and the performances had begun to twitch. He wanted to catch people slipping. Cracking. Failing to finish their sentences. And in that house on Woodrow Wilson Drive, they did.

There is a chandelier in the dining room. There is a bar, worn smooth. There are windows that catch the filtered sun through canyon trees. Outside, a pool with no pretense to glamour. Just water. Just the sound of it moving.

Friends came and went. Peter Falk. Ben Gazzara. Seymour Cassel. Faces you saw over and over in the films because loyalty, for Cassavetes, was a creative principle.

And Rowlands—always Rowlands—turning herself inside out in the middle of the kitchen. That black and white tile. The same floor on which she collapsed, which she raged against, which she danced across, in one film or another. It hardly matters which.

Cassavetes was not polished. He wore rumpled jackets, open collars, a cigarette often burning down in his fingers like a slow fuse. There was an intensity about him that didn’t read as performance—it was closer to compulsion. He laughed loudly, argued fiercely, loved with visible force. Friends spoke of his charm, his volatility, his unrelenting need to push people past what they thought they could do. He was magnetic, exhausting, the kind of man who didn’t take no for an answer because he wasn’t asking. His style—like his films—was immediate, emotional, raw at the edges. He didn’t care for appearances, only for truth, and even then, only if it cracked something open.

Cassavetes funded Faces with his own money. Mortgage money. He shot Shadows on borrowed time. Opening Night was cut at the house, late into the night, over drinks that had stopped being celebratory. The house absorbed it all—the shouting, the silence, the unresolved endings. It was not about polish. It was about presence. Real time. Real stakes.

There is a mural in the bathroom now, painted by a relative. Seven women, including Rowlands. A tribute, yes, but also a timestamp. A reminder that this house was not curated. It was lived in. Hard.

When Rowlands died, the house went still. Now it is for sale.And like all endings in a Cassavetes film, it arrives quietly—but leaves something unsettled.

“I’m not really interested in the camera. I’m interested in people. I’m interested in what makes them work, and what makes them hurt.” —John Cassavetes

For Sale at $4,995,000 with Compass

"You don’t buy this house. You live where the voices still echo.”

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowland in their Hollywood home