The Aristocracy for Sale: Downton Abbey and the Commerce of Class

Lord Carnarvon, owner of Highclere since 1842, who was the chief financial backer on the Tutankhamun excavations.

All Images Courtesy of Bonhams

The auction of Downton Abbey costumes is more than television memorabilia. It reveals how English aristocracy has become a global luxury product, where old money inherits tradition and new money buys its aura.

Michelle Dockery (as Lady Mary): Assortment of nightwear, including two Kimonos

Shirley MacLaine (as Martha Levinson): Two evening dresses, in teal and seafoam green

Peter Joseph Egan (as Hugh MacClare 'Shrimpie'): Two Scottish formalwear costumes

Hugh Bonneville (as Lord Grantham): Set of cricket whites

Michelle Dockery (as Lady Mary): Wedding dress and accessories, worn for the marriage of Lady Mary Crawley to Matthew Crawley

Jessica Brown Findlay (as Lady Sybil): The 'Harem' pants

It would be easy to mistake the forthcoming auction of Downton Abbey costumes and memorabilia for an exercise in television nostalgia, the genteel equivalent of emptying the dressing-up box of a provincial museum. And yet that misses the deeper oddity of the event. These garments — frock coats, tiaras, beaded chemises — were never really “props.” They were, and are, costumes in the most serious sense: disguises that permitted their wearers to inhabit a simulacrum of aristocracy so convincing that millions across the world believed they had been granted access to England’s secret upstairs-downstairs truth.

Now these disguises are on the block, and the transaction reveals more than the producers ever intended. For Downton Abbey was always less a drama than a brand extension of English country house culture — that elaborate theatre of deference and decay. To buy one of these garments is not merely to own a relic of a television phenomenon. It is to participate, however faintly, in the purchase of aristocracy itself.

Of course, the true aristocracy would never sully themselves by such a thing. They have no need to buy their own history back, still less a televisual counterfeit of it. A Cavendish or a Howard does not queue for the wardrobe cast-offs of a television studio. Their closets sag with their fathers’ dinner jackets and their brothers’ mended tweeds, each garment stitched with the frugality of inherited status. Garments worn thin but dignified by repetition. The real Highclere, after all, belongs to the Carnarvons — a family whose laurels include financing the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. While today’s bidders are buying into an imitation aristocracy, the Carnarvons once dabbled in a dynasty that made even England’s earls look provisional.

This auction is therefore not for them but for the global aspirant class — the hedge funder in Manhattan, the oligarch with a Belgravia pied-à-terre, the Qatari royal whose equerries already fill Highclere Castle during the season. What they are acquiring is not a frock but a fragment of a myth: the fantasy of legitimacy conferred by centuries of inherited land and languid entitlement.

Library: A selection of set dressing acquired by the Prop Department

A selection of children's props Used by the characters Sybbie, George, Marigold and Caroline

A selection of 20th century cocktail and drinks props

An extensive King's Pattern silver plated part canteen. From Season 1 onwards

The paradox, as ever with England, is that the myth has always been more robust than the reality. Downton Abbey was celebrated for its historical accuracy, but what it really offered was a more flattering fiction: aristocracy without bankruptcy, servitude without resentment, heritage without dry rot. The show became an export commodity, a soft-power arm of VisitBritain. The auction is merely the next phase of this commodification, proof that even the most ineffable codes of class can be packaged, catalogued, and hammered down at Sotheby’s.

In this light, the sale becomes less about the past than about the present global marketplace of desire. One can easily imagine a Newport mansion whose drawing room already overflows with Gainsborough reproductions and ormolu sconces now gaining a “Lady Mary” evening dress, displayed under glass like a saint’s relic. Or a Hong Kong penthouse where Carson’s butler’s livery hangs in a closet, a kind of aristocratic cosplay for the host who wishes to give his dinner parties an extra tincture of Englishness.

That, in the end, is what is being traded: not textiles, but atmosphere. A buyer is purchasing the scent of polish in the long gallery, the clink of port in a panelled library, the creak of boots on a flagstone hall. They are acquiring a script for how to behave as though they had been born to it. And if this seems faintly ridiculous — well, so too is the spectacle of English nobility itself, which has always been theatre.

Michelle Dockery (as Lady Mary): A selection of graphics production made by Downton Abbey's Graphics Department

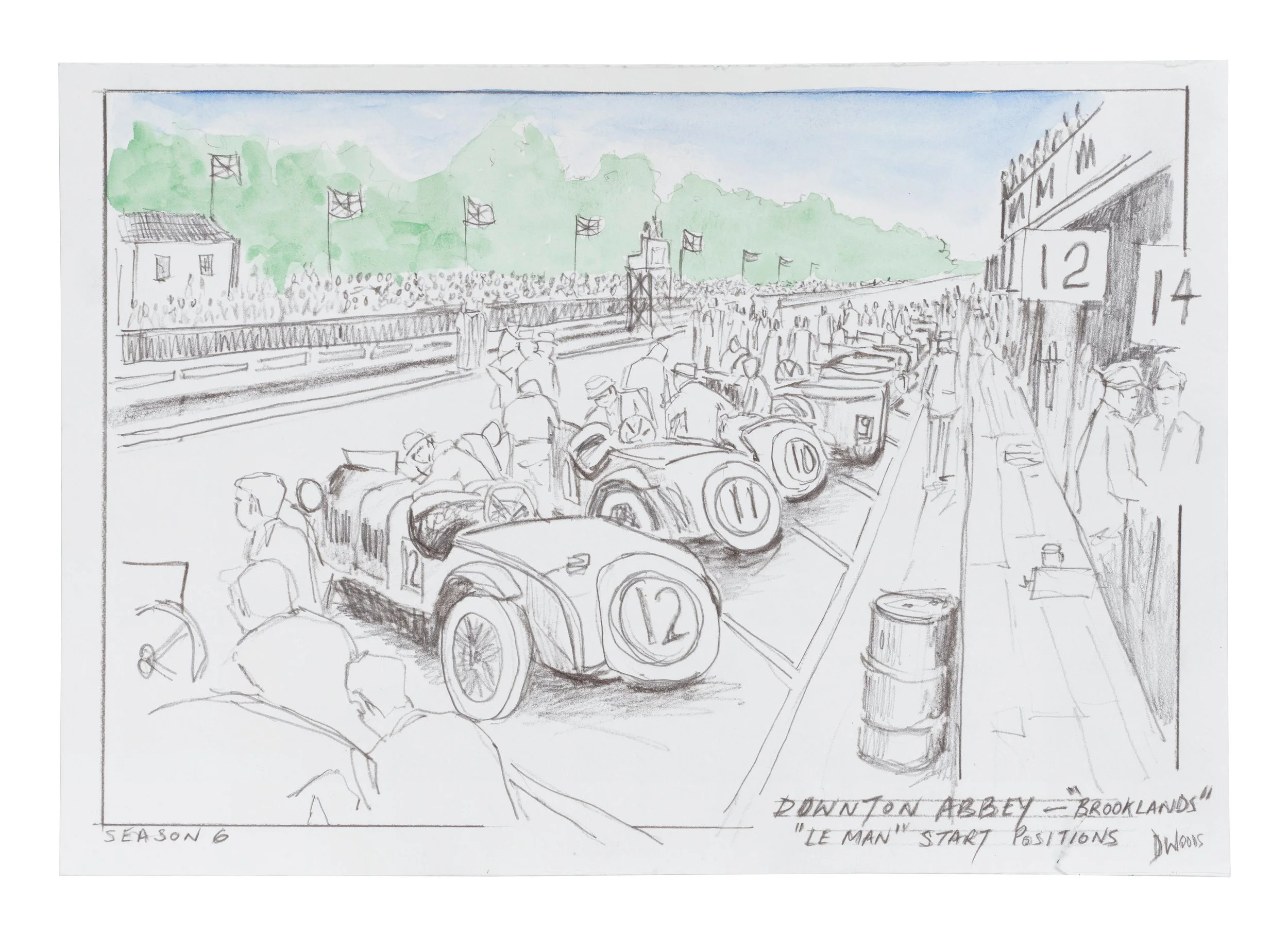

Donal Patrick Woods. A preparatory sketch for the Brooklands Le Mans start positions, Season 6, Episode 7

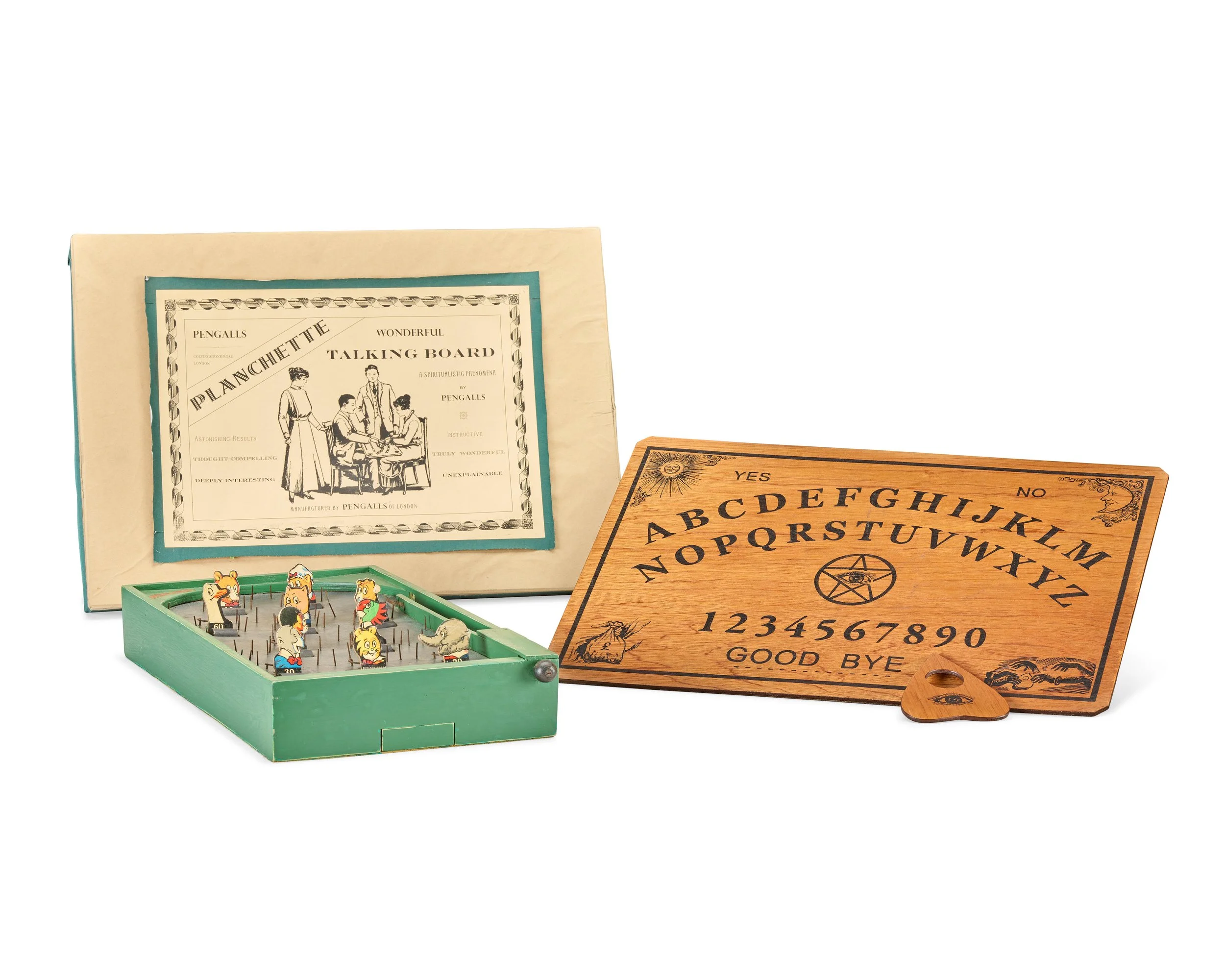

The 'Talking Board' used in the Servant's Hall in Season 2, Christmas Special

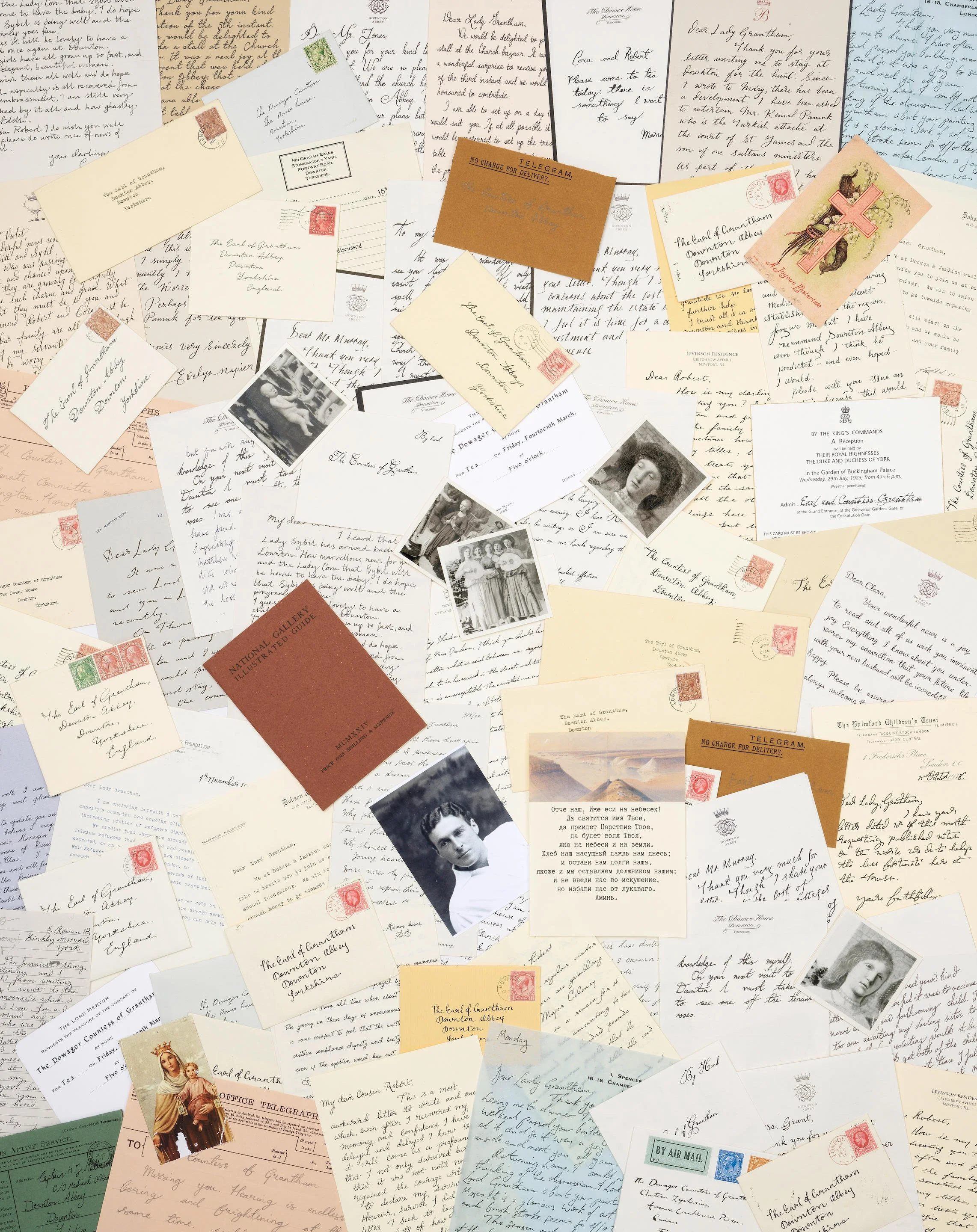

A selection of letters and ephemera production made by Downton Abbey's Graphics Department

Perhaps the only honest way to see the auction is as a continuation of that theatre: the great aristocratic comedy, now performed with props made not in Savile Row but in Shepperton studios. These are not heirlooms, they are costumes — merchandise masquerading as heritage. One does not have to believe in the old order to pay handsomely for its trappings. It is enough to desire the aura. And aura, unlike bloodlines, can be bought. In England, class has always been theatre — only now, the tickets are on sale.

16th September 14:00 BST with Bonhams

“The aristocracy is not dying; it’s franchising. And in England, as ever, the show goes on.”

All Images Courtesy of Bonhams

The Grantham Family Car 1925 Sunbeam 20/60hp Saloon