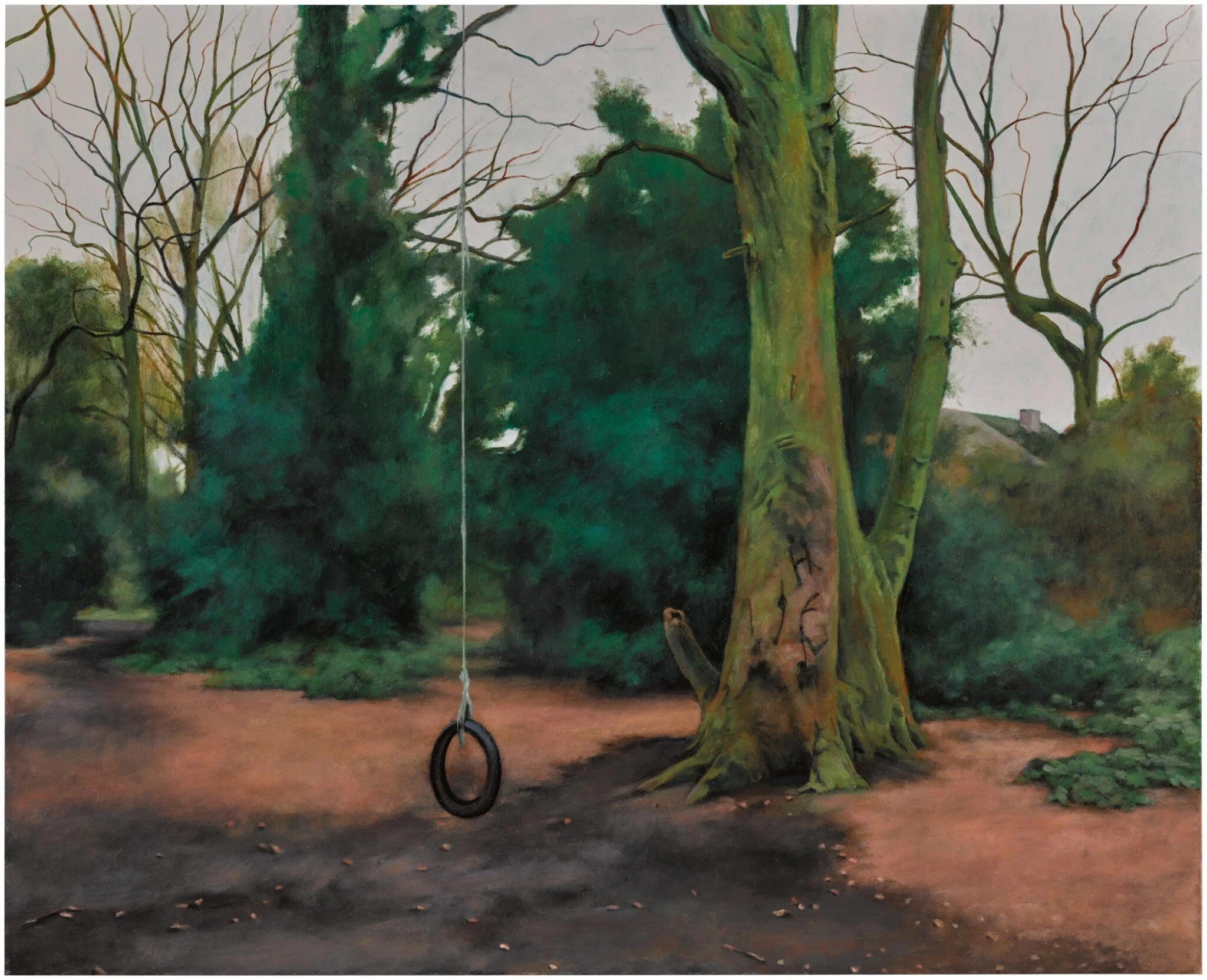

“Nothing Happens. And Then It Happens Again.”

GEORGE SHAW The Goal Mouth Revisited, 2019-2021

Images Courtesy of Anthony Wilkinson Gallery

Exploring the meticulous suburban landscapes of George Shaw, where childhood memories and everyday English life are captured with painstaking detail in Humbrol enamel, transforming the ordinary into profound reflections on time, absence, and belonging.

Scenes from the Passion: Sunday Evening, 1998

Landscape with Dog Shit Bin, 2010

George Shaw paints with Humbrol enamel. Let’s start there. It’s the kind of paint your childhood best friend’s older brother used to lacquer Airfix Spitfires with on rainy Saturdays. Not artist-grade oils or Berlin-washed acrylics. Humbrol. Small tins. Glossy. Toxic. Sticky in the wrong humidity. Basically the DIY of fine art media.

And yet: Shaw uses it to recreate the most lovingly, maddeningly ordinary slices of suburban British life. Tile Hill, Coventry. His childhood estate. Repeat. Tile Hill in fog. Tile Hill after rain. Tile Hill in what looks like the precise 11 minutes between a chippy fight and bin day. It’s not nostalgia, exactly—it’s memory weaponised. Enamelled.

You don’t walk into a Shaw and go wow. You go hm. You stare. Then the discomfort settles in. Something’s off. Not technically—technically it’s near-flawless—but emotionally. There’s no one there. Not a soul. Not even a leaf out of place. But the absence is specific, like someone left a minute ago, and they’re watching you from just behind the hedgerow.

His best-known series—Scenes from the Passion—sounds like it might be biblical, except it’s actually a meditative grind through bus stops, garages, chain-link fences, and pub backsides that no one takes pictures of unless they’re being ironic. But Shaw’s not ironic. He’s something worse: sincere.

“I Paint the Places Where Nothing Happened.”

He said that once, or something like it. Except what happens in Shaw’s work is that you realise everything happened. The graffiti isn’t just tagging—it’s a remnant of adolescence. The path behind the shops isn’t just municipal—it’s where you smoked your first cigarette, broke your first arm, saw your first ambulance. These are emotional palimpsests in municipal form.

And because they’re painted with Humbrol—a paint that doesn’t allow for flourishes, second chances, or mistakes—the scenes are stiff with intention. He can’t rework it. He can’t sand it back. It’s brittle, stubborn, chemical.

Which makes them even more like memory: indelible, uneven, strangely glossy.

Ash Wednesday: 7am, 2004-5

George Shaw in the studio

Contemporary Art’s Reluctant Archivist

Shaw isn’t fashionable, except now he kind of is. Which is its own irony. In 2024, his works—modest in ambition, but relentless in execution—sold at multiples of estimate at Phillips and Christie’s. Small panels, mostly. Scenes like The Lych Gate and Mark’s Backyard fetch sums that would pay off the very mortgages they depict.

This is not because the market suddenly discovered suburbia. It’s because Shaw’s work performs a cultural double-backflip: it makes the viewer complicit. You don’t admire his paintings. You inhabit them. You remember being there, even if you weren’t. That’s a dirty trick. It’s also genius.

Shaw isn’t a 19th-century realist. His paintings don’t document—they mourn. Too precise to be sentimental, too personal to be purely documentary, they reject the new and the flashy. No Instagram filters, no ironic flourishes. Just brick, sky, wet pavement—and a silence where people once were.

In a world drowning in noise and flash, Shaw’s work is the quiet opposite: repetition, stillness, and subtle mood. His paintings meditate on memory and place. The enamel paint almost feels like a language—if you don’t get it, you just see a flat surface. But if you do, you see everything.

Shaw is what happens when childhood becomes a kind of aesthetic rulebook. He’s the poet of English flatness—in space, tone, and feeling. And yes, nothing happens.

And then, it happens again.

“And yes, nothing happens. But that nothing? It’s rendered with exquisite care.”

GEORGE SHAW Why Don't You...?, 2021