From Superflat to Super Stage: Takashi Murakami’s Leap from Prints to Pop Canon

The Artist Takashi Murakami

All Images Courtesy of Wrights Auctions

As his candy‑colored worlds move from intimate editioned prints to monumental reimaginings of Japanese art history at Gagosian, Murakami is increasingly being positioned alongside Warhol, Lichtenstein, and Haring — and the market may be catching on.

Takashi Murakami b.1963 And then and then and then and then and then (Aqua Blue) 1999 Estimate: $1,000–1,500

Takashi Murakami b.1963 Kyoto Kōrin Mononoke Flower 2023 Estimate: $800–1,200

Takashi Murakami’s worlds are at once innocent and menacing — candy‑colored universes where cartoon flowers grin too widely and skeletal specters drift in on pastel clouds. Beyond the Dimensions bathes the eye in his signature saturation: smiling blossoms radiate outward in near‑perfect symmetry, each petal a note in a hyper‑pop chorus. In Behold! ’Tis the Netherworld, the mood tilts darker. The same meticulous linework summons grinning skulls that float like celestial ornaments, their cheery menace softened by a watercolor‑bright palette.

These works — editioned prints, intimate in scale — are pure Murakami: a seamless blend of manga aesthetics, traditional Japanese painting techniques, and the relentless surface appeal of pop art. This is his Superflat philosophy in action: depth and hierarchy flattened into a single, vibrant plane where the decorative and the philosophical coexist. It’s a language that draws equally on Edo‑period screens, postwar pop culture, and otaku subculture — then distills it into images so precisely engineered they seem almost digitally generated.

Yet behind their glossy perfection lies an artist deeply attuned to history. Murakami is not simply a maker of pop‑friendly icons; he is a cultural historian in the guise of a contemporary painter, one who treats the space between “high” and “low” culture not as a gap to bridge but as fertile ground for invention.

That is why the appearance of these works in Wright’s August 6 “Editions & Works on Paper” sale is telling. In print form, they are accessible, priced in the low thousands — approachable for collectors who might not yet venture into the six‑ or seven‑figure realm of his large‑scale paintings. But in style and intent, they carry the same DNA as his most ambitious works.

Those ambitions were on full display this past year. In winter, Gagosian London presented Japanese Art History à la Takashi Murakami, a glittering collision of Edo‑period elegance and manga‑inflected exuberance. Traditional compositions re‑emerged in shimmering pigments, reframed with Murakami’s trademark flowers, skulls, and surreal characters.

By spring, in New York, he expanded this dialogue with Japonisme → Cognitive Revolution: Learning from Hiroshige. The exhibition comprised 121 works reinterpreting Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. These were not polite homages. Murakami’s smiling blossoms swarmed through river valleys; skull clusters floated over cherry‑blossom vistas. Ukiyo‑e landscapes collided with the visual language of street fashion, animation, and pop spectacle. It was tradition in warp drive — Edo‑era art catapulted into the fluorescent present.

Andy Warhol 1928–1987 One plate (from the Love portfolio) 1983 Estimate: $15,000–25,000

Tom Wesselmann 1931–2004 Blonde Vivienne 1988-89 Estimate: $12,000–18,000

James Rosenquist 1933–2017 North (from the F-111 series) 1974 Estimate: $4,000–6,000

Ed Paschke 1939–2004 Indigo Deux 1988 Estimate: $800–1,200

The leap from Wright’s editioned works to Gagosian’s wall‑filling canvases is not simply one of scale. It marks a shift in register, from the collectible object to the cultural event. The Wright prints embody Murakami’s Superflat ethos — art stripped of hierarchy, equally at home on a museum wall or a bedroom shelf. The Gagosian shows take that same philosophy and amplify it to a scale that commands not just a room but an entire cultural season.

Murakami has always thrived in these in‑between spaces: between pop culture and fine art, between cheerful kitsch and apocalyptic symbolism, between affordability and aspiration. That duality is visible in his market too — and in Wright’s August 6 catalogue, it’s also visible on the page. Here, Murakami’s Beyond the Dimensions and Behold! ’Tis the Netherworld share space with Warhol’s candy‑colored Cow, Lichtenstein’s comic‑strip cool, and Haring’s graffiti‑born graphics. It is a curatorial placement that quietly positions him as a successor in the Pop Art conversation, his smiling flowers and skull‑strewn dreamscapes now catalogued alongside the canonical icons of post‑war visual culture.

Murakami’s fluency in both art and commerce was perhaps most famously demonstrated in his long‑running collaboration with Louis Vuitton. Beginning in 2003 under Marc Jacobs’ creative direction, he transformed the maison’s monogram into a kaleidoscope of colour, populated with his signature smiling flowers, cartoon pandas, and playful cherries. The partnership blurred boundaries between fine art and luxury fashion, turning handbags into collectible art objects and boutiques into temporary galleries. It was a cultural crossover that expanded Murakami’s audience far beyond the white cube — and cemented his position as a master of translating artistic language into global, desirable product. That same seamless interchange between high culture and pop‑commercial appeal still underpins the work on paper at Wright and the monumental canvases at Gagosian

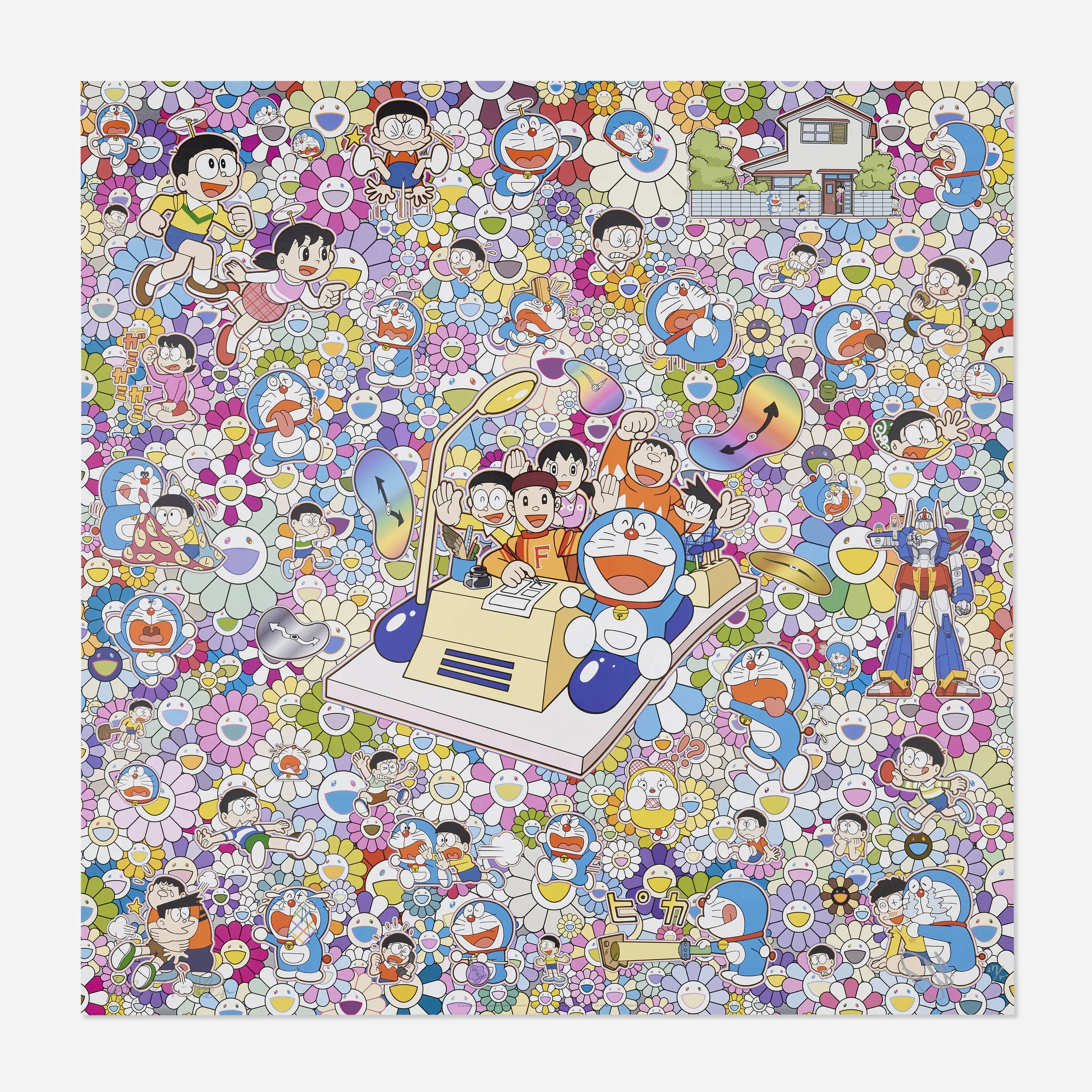

Takashi Murakami b.1963 On an Endless Journey on a Time Machine with the Author Fujiko f. Fujio! 2018 Estimate: $1,000–1,500

Takashi Murakami b.1963 Jellyfish Eyes (White 1); Jellyfish Eyes (White 3) (two works) 2006 Estimate: $1,200–1,800

Today, a collector can pick up a Murakami print for under $2,000, while his large‑scale works climb into the millions. The gap between those two tiers may be narrowing. With two major Gagosian exhibitions in less than a year and critical attention running high, visibility has rarely been greater. Meanwhile, supply of top‑tier works remains tightly controlled. For collectors, that combination — heightened cultural presence and limited availability — has historically been a precursor to upward price pressure.

Seen in that light, the Murakami prints at Wright are more than bright, pop‑surrealist flourishes. They are compact expressions of a practice that now commands global stages. They are also, perhaps, a moment of opportunity — a way to enter the world of an artist whose work is increasingly being positioned not just alongside contemporary peers, but alongside the giants of post‑war art.

Ends 6th August August 12:00 GMT with Wrights