The Pop Icon Meets the Surrealist Lens: Warhol’s Man Ray at Sotheby’s

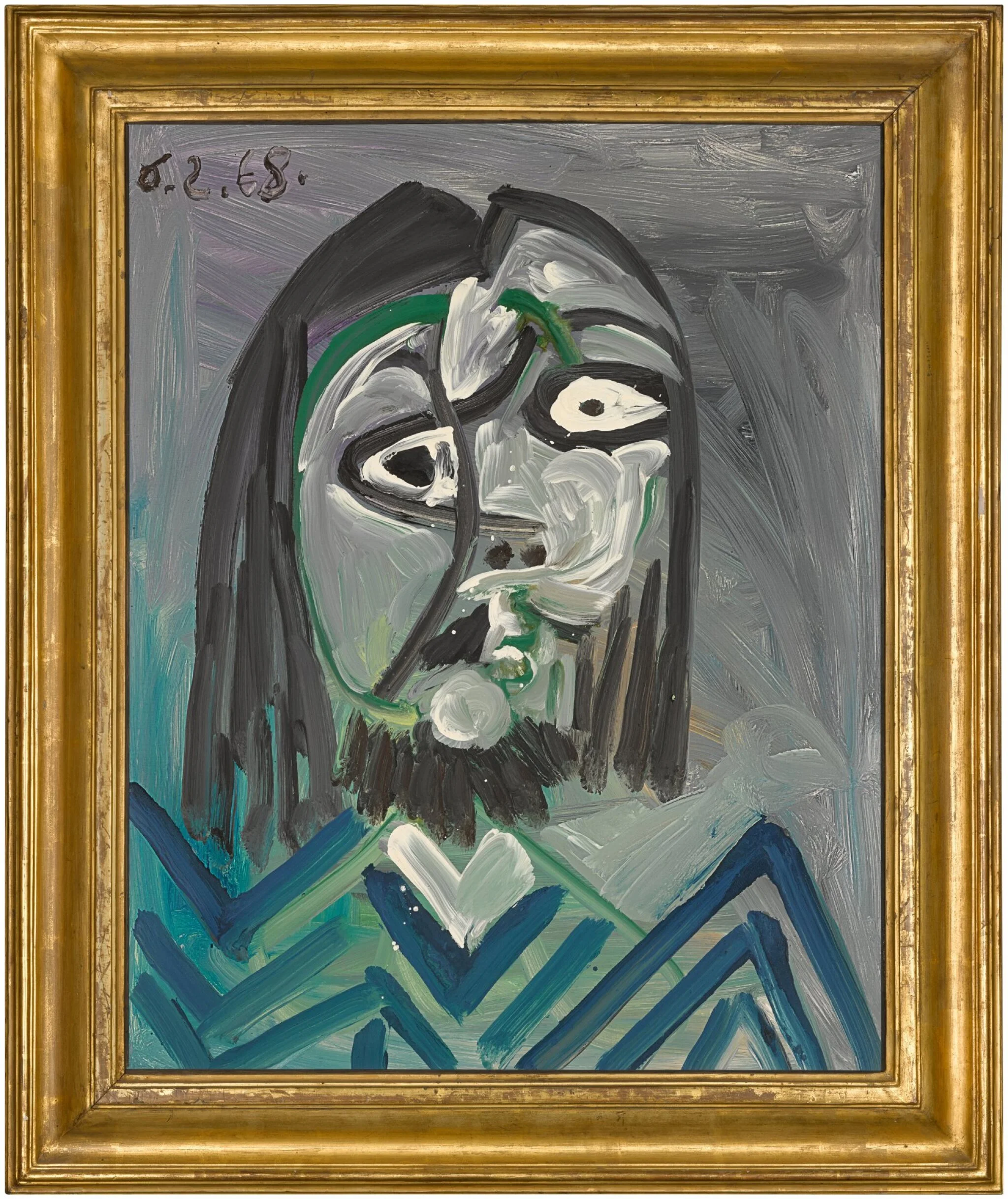

René Magritte Tête. Estimate £500,000

All Images Courtesy of Sotheby’s

As Sotheby’s brings Pauline Karpidas’s collection to auction, Warhol’s 1974 portrait of Man Ray resurfaces — less a painting than a sly salute from one master of image to another.

Polaroid of Andy Warhol and Man Ray © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol Man Ray. Signed, titled, numbered 6/6 and dated 74

There are plenty of ways to turn another artist into a trophy—buy them, bury them, plagiarise them—but Andy Warhol, at his most interesting, preferred to hang them in the shop window and let the world gawk. His 1974 silkscreen portrait Man Ray, now up at Sotheby’s in the Pauline Karpidas sale, is that rare act of homage in a market that usually smells more of trophy-hunting than of conversation.

The picture is exactly what the label says: Man Ray’s head, half in photographic shadow, half in Warhol’s knowing colour fields, squared up to a metre each way. Six examples exist; this is number six of six. You can trace the provenance like a dotted line through post-war art dealing: Milan’s Galleria Il Fauno, Alexandre Iolas—the smooth-voiced éminence grise who could place a work with an heiress before the paint was dry—then Maria Tognoli, a Turin collector of that brisk Italian breed who mixed modernism with couture. By 1999 it had passed through Sotheby’s before being netted by Karpidas herself for her London home.

Karpidas, a collector with an eye less for consensus than for idiosyncrasy, made her fortune in fashion and spent it with a hunter’s relish. Her London Collection—fifty-five lots of Bellmer, Magritte, de Chirico, Dalí, Koons, and the other usual suspects—reads like a salon of twentieth-century surrealism and its pop-descendants. She bought with her instincts, not a focus-group’s: the market has since caught up, as the nine-figure estimates make clear.

Karpidas bought with instinct, not hedge-fund spreadsheets, and her sale now is a parade of market-certified names. The Warhol/Man Ray is pegged at £400,000 to £600,000—small change beside the Magrittes at eight figures, but culturally it’s one of the more intelligent dialogues in the room.

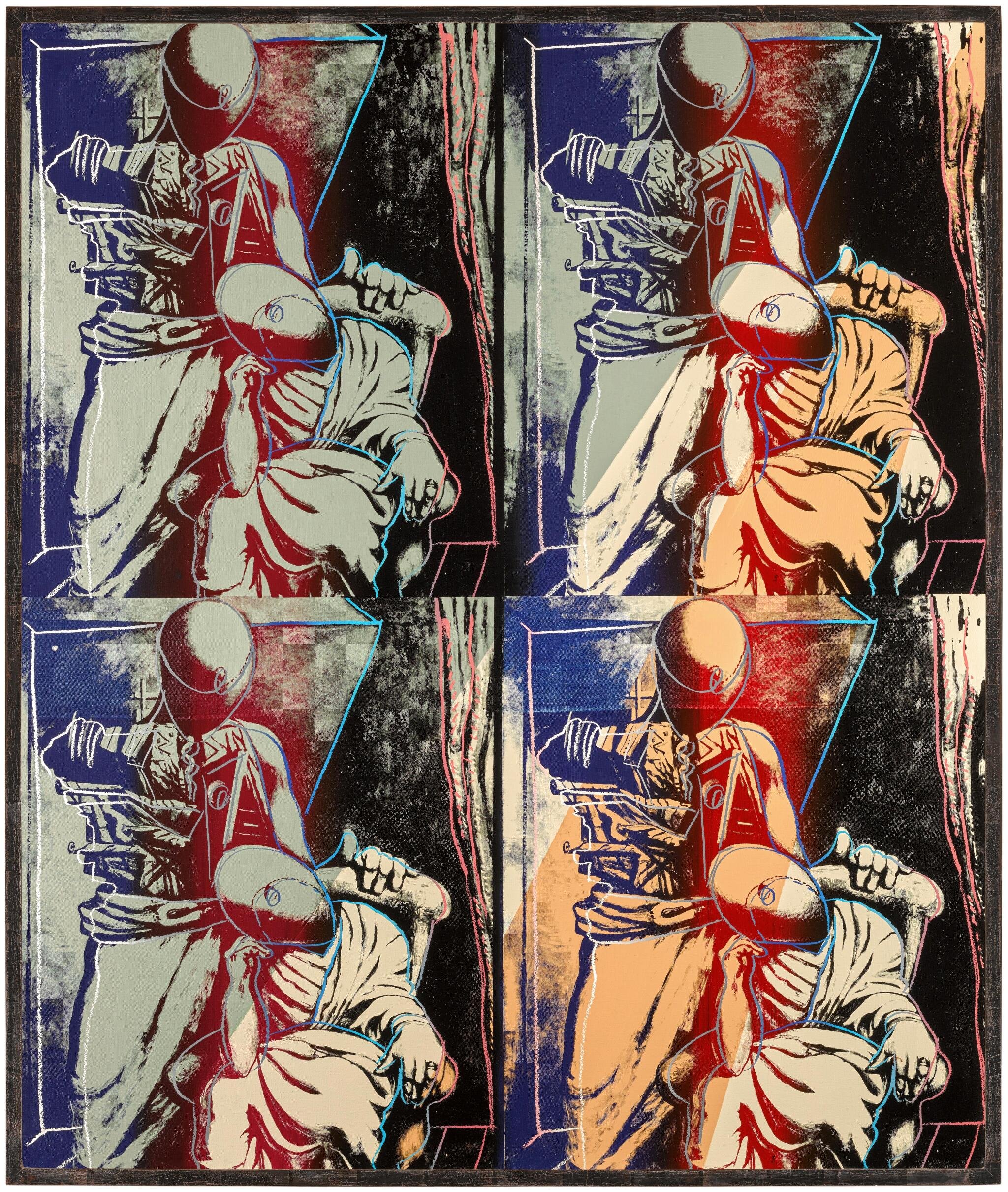

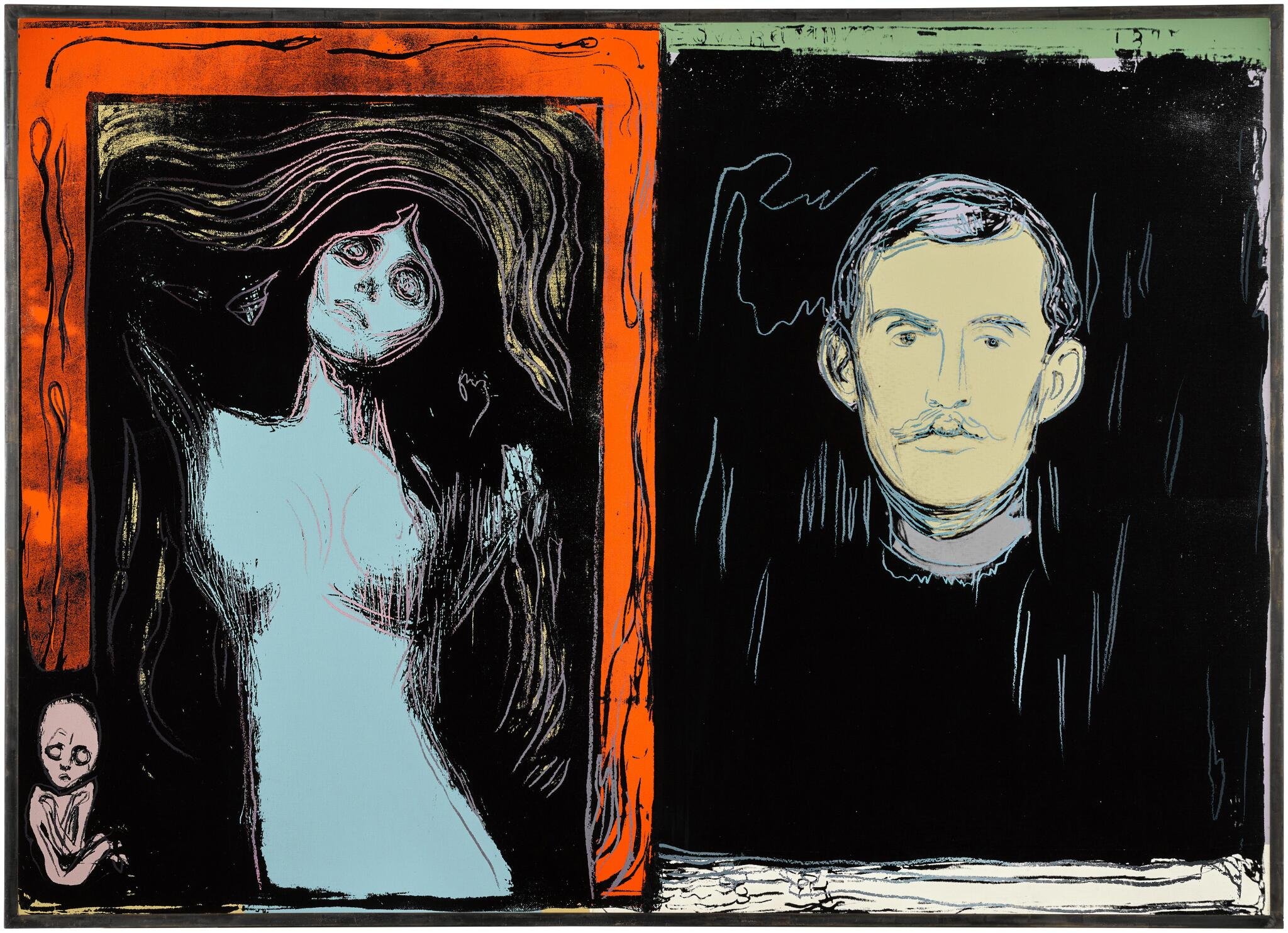

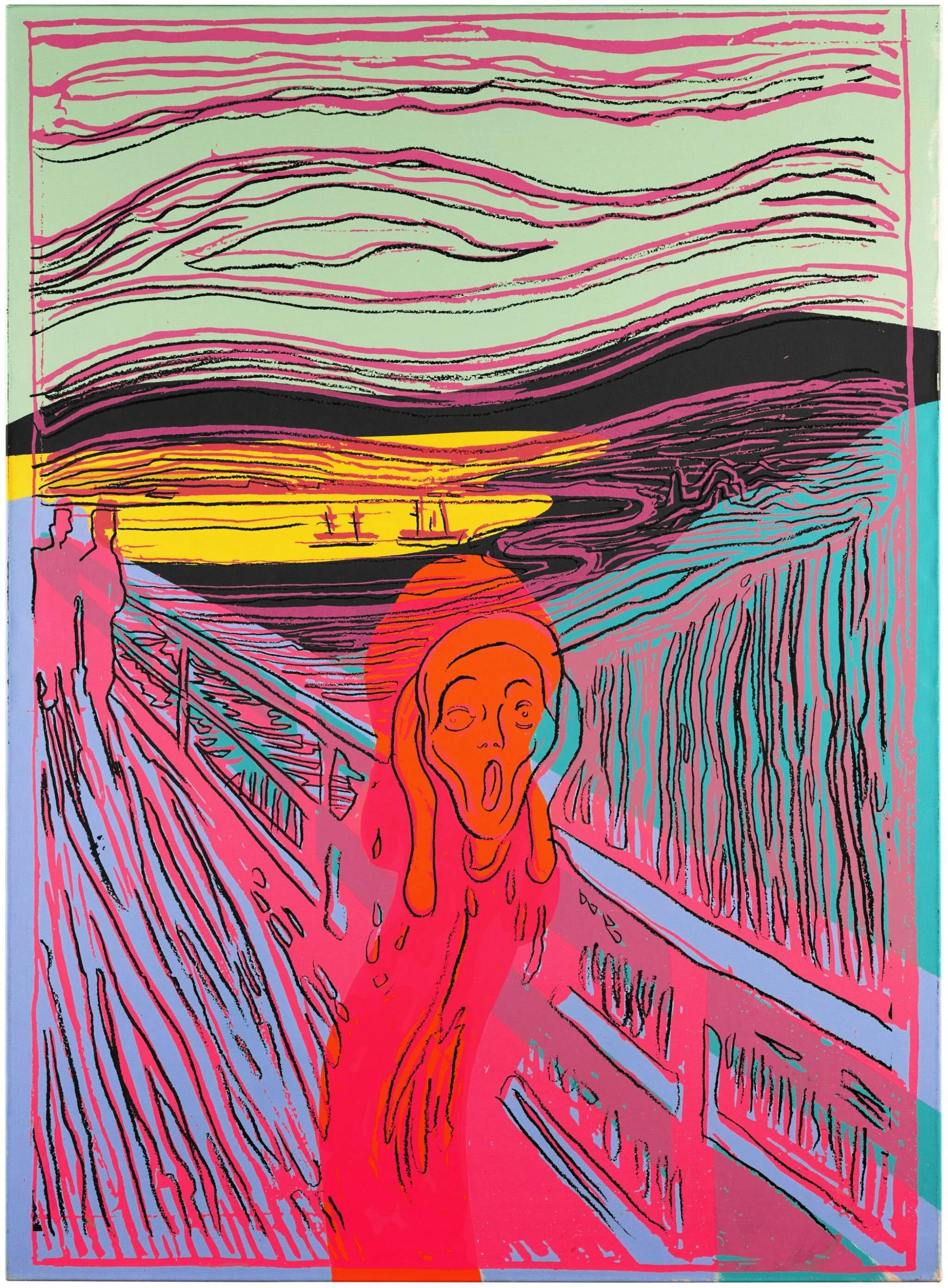

Warhol had already mined the art-historical canon in his Munch series, his de Chirico reinterpretations, and that sly dalliance with the Mona Lisa. But with Man Ray he wasn’t looting so much as staging. Warhol knew Man Ray was a fellow image-maker who blurred the line between art and the gloss of commerce—fashion photography, portraits of the rich, but also the cold precision of the readymade. Warhol’s reverence went beyond the commission. He owned more than two dozen Man Ray photographs—sold in his estate sale—and kept the painter’s Peinture Féminine (1954) in his sitting room. He admired Man Ray’s pre-war portraits of Picasso, Dora Maar, Kiki de Montparnasse—the Paris equivalents of Warhol’s Marilyns and Jackies. Both men understood the power of the image as social currency. But Warhol also indulged in the kind of dry inversion that kept critics guessing: “I only loved him because of his name—Man Ray.” Like “Marilyn” or “Brillo,” the syllables were branding gold, short, sharp, mysterious.

Andy Warhol 'The Poet and His Muse (After de Chirico)'. Estimate £800,000

Andy Warhol 'Madonna and Self-Portrait with Skeleton's Arm (After Munch)'. Estimate £2,000.000

In this portrait, Warhol lets Man Ray’s own poker-faced modernity remain intact, the silkscreen process only heightening the play of anonymity and celebrity.It was first shown in Milan in 1974 in an exhibition literally titled Man Ray by Andy Warhol. The poster showed the same cropped head—two artists, one image, no clear hierarchy. In an art world still bent on overthrowing the past, Warhol was saying: sometimes the past is the point. The gesture was part vanity mirror, part relay baton.

The sale’s broader mood is one of that now-familiar auction-house theatre: the gilt catalogue, the long parade of “Formerly in the collection of…” to lend each lot a genealogy. But if you strip away the velvet ropes and the whispered estimates, the Man Ray is a reminder that citation can be more than a market move. In an age when everyone with a smartphone thinks they’re Duchamp, Warhol’s act of framing another artist’s face was a signal: respect the lineage, even as you silk-screen it in hot pink.

There is, inevitably, irony here. The picture celebrates a man who delighted in making art that could not be reduced to decor—now destined for some very expensive wall as very expensive decor. Robert Hughes would have said, “The market has the digestion of a goat,” and he’d be right. The Karpidas sale is a feast of goats’ favourites: shiny, recognisable, saleable.

Andy Warhol The Scream (After Munch). Estimate on £3,000,000

Pablo Picasso Buste d'homme. Estimate on £2,500,000

Still, every so often the market coughs up a work whose intelligence outlives its price tag. This is one. Warhol was at his best when framing others—Marilyn, Mao, the electric chair, even himself—as if to say: the frame is the real subject. In Man Ray, the frame encloses not Hollywood or politics but a fellow artist, one whose camera had once framed his own century. That choice alone tells you more about Warhol’s seriousness, and slyness, than a dozen Campbell’s cans. It’s a picture about seeing—and about who gets to do the looking. That’s a lesson worth the hammer price, whatever it turns out to be.

17th September 16:00 BST with Sotheby’s

“I only loved him because of his name — Man Ray.”

Andy Warhol

All Images Courtesy of Sotheby’s

René Magritte La Statue volante. Estimate of £12,000,000

Pauline Karpidas: The London Collection Evening Auction