Edward Molyneux: Elegance, Silence, and the Art of Concealment

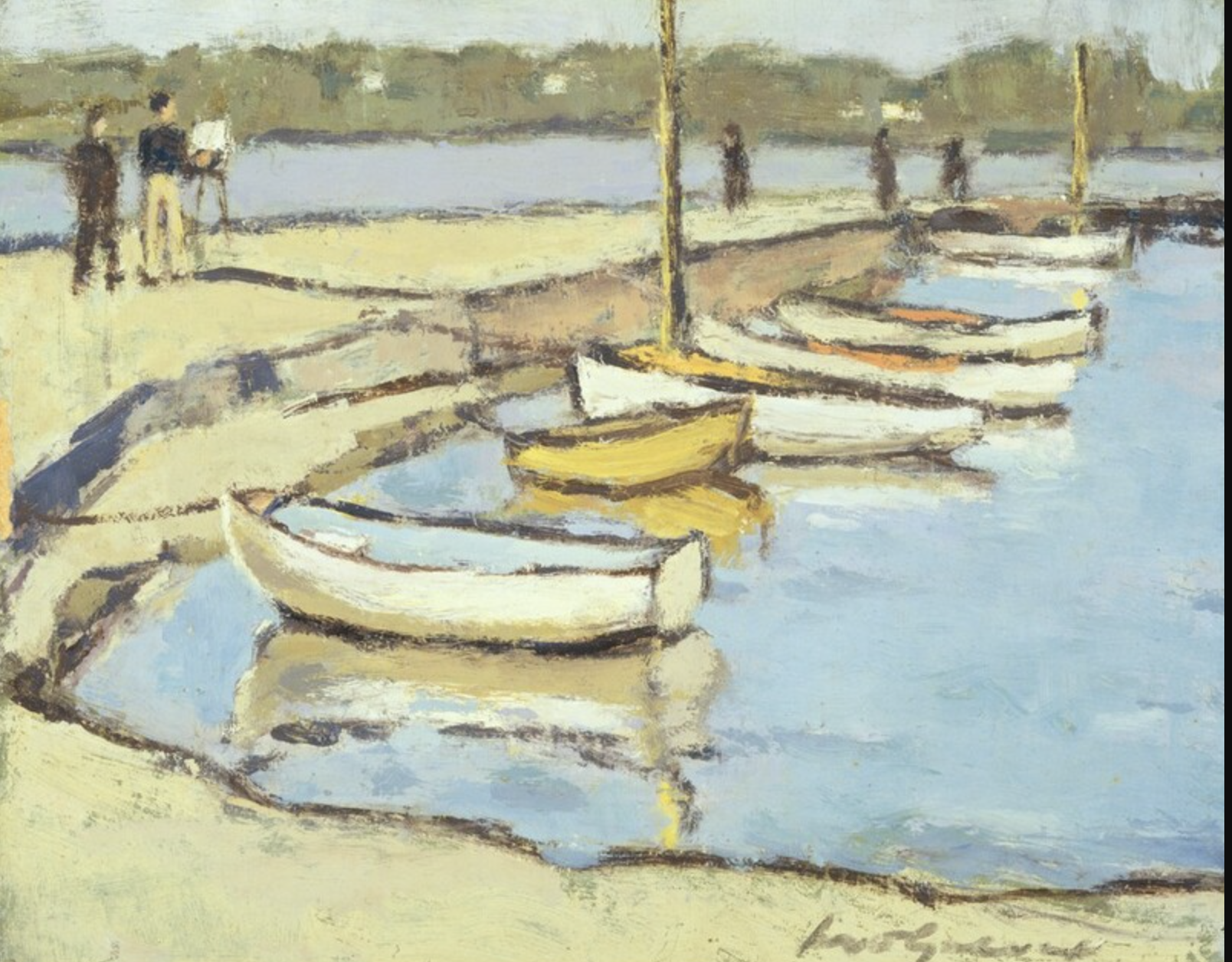

EDWARD MOLYNEUX Artist on a Quay, 1962/1964

Images Courtesy of National Gallery of Art

A master of refinement whose paintings and designs speak quietly of identity, desire, and the unspoken truths shaped by discretion and grace.

Chapel In Provence, 1962-64

Laundry Boats on The Seine

Edward Molyneux’s paintings—spare, elegant, almost ascetic—are exercises in restraint. Better known for his sartorial genius than his brushwork, the artist’s oeuvre reveals an intimate counterpoint to the glitz of fashion. His canvases offer a delicate narrative of survival, expression, and the search for belonging, shaped by the constraints of time, society, and self.

Molyneux’s homosexuality, discreet during his lifetime yet inseparable from his artistic voice, is not signalled through overt iconography but through a palpable tension—a language of eloquent silence. His work gestures toward a world of coded communication and hidden desires, mirroring the conditions of queer existence in early 20th-century Europe. The restrained palette, the elegant forms, the deliberate emptiness: all speak to a self negotiated between revelation and concealment.

Though private by nature, Molyneux moved effortlessly within the highest echelons of society. His clientele ranged from European royalty—Princess Marina of Greece and the Duchess of Kent—to Hollywood icons such as Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. These relationships were woven into a complex social tapestry where Molyneux’s artistry extended beyond fabric to influence and companionship. In salons and soirées, his refined taste and discreet charm positioned him at the crossroads of glamour and discretion, a man who negotiated identity as deftly on canvas as in society.

Boats: Silent Voyages Across Time

Molyneux’s depictions of boats transcend simple maritime subjects. They become metaphors for transience, travel, and the thresholds between worlds. Their quiet hulls and taut rigging hover in a liminal space—neither fully at sea nor safely docked. These vessels reflect the artist’s own navigation of a life constrained by an era hostile to his true self: charting a course both public and profoundly private.

The stillness of these boats, set against empty waters or blank skies, is at once literal and symbolic. They are simultaneously vessels of escape and instruments of entrapment, poised between motion and stasis. Their empty decks become silent stages for meditations on solitude and longing.

A Rose, 1953

Chinese Statue of a Bird. 1953

Still Lifes: Objects as Oracles

In Molyneux’s still lifes, the ordinary is transfigured into the emblematic. A glass, a bowl, a single flower—each becomes more than form; each is a silent oracle speaking of fragility and permanence. These compositions evoke a subtle dialogue between the animate and inanimate, between what is held and what is lost.

Rendered with the same refined simplicity that characterised his fashion designs, these objects suggest a yearning for clarity amid complexity. Their muted palettes and precise contours assert a calm order, offering contrast to the turbulence quietly coursing beneath the surface.

Market Rarity and Resonance

Edward Molyneux’s paintings rarely come to market, a scarcity that only heightens their allure among collectors and institutions. This rarity owes something to his relatively modest artistic output in comparison to his lengthy career as a couturier, and to the many works held privately. When a painting does appear at auction, it attracts serious interest—not solely for its aesthetic refinement but also for the rich historical and cultural narrative it embodies.

Collectors recognise that Molyneux’s work sits at a unique crossroads: early 20th-century modernism, discreetly coded queer identity, and the elegance of high society patronage. Unlike flashier or mass-produced art, his paintings reward patient contemplation and carry a quiet gravitas that resonates with discerning buyers. This blend of artistic merit, historical weight, and market scarcity explains why his works command strong prices and sustain value over time.

One notable example is a rare oil study of an evening dress attributed to Molyneux from the 1930s. Estimated at around £30,000, it sold for nearly double, prized both as a fashion study and a window into Molyneux’s artistic sensibility beyond the runway. Similarly, a still life featuring flowers and glassware, emblematic of his understated style, recently fetched a price well above estimate at a prestigious European auction, signalling growing recognition of his dual career.

Chinese statue of a dog, 1953

Still life of lemons and vessels

Molyneux’s Quiet Revolution

Edward Molyneux’s life and work unfold in the spaces between things: public and private, appearance and essence, desire and discretion. His homosexuality—never publicly declared, often encoded—was lived in a world that demanded silence and camouflage. To understand his paintings is to read this silence not as absence but as presence shaped by omission.

In an age when visibility was perilous, Molyneux mastered invisibility. His paintings stand as documents of that mastery—a disguised defiance, a life lived in soft focus. There is something distinctly American about this restraint: a cool composure that veils a tumult beneath.

His stillness is a language of survival, a refusal to be diminished. Every muted stroke asks the cost of visibility and asserts the power of what remains unseen.

Molyneux’s legacy is not merely in what he created, but in what he quietly declined to reveal. It is a revolution painted not with loud gestures, but with the steady hand of discretion.

"In Molyneux’s work, silence is not absence but presence—a deliberate, elegant language of what remains unspoken."

Edward Molyneux A Rose, 1953